Сравнительный анализ концептуальной плексности и грамматического числа в русском и английском языках

Сравнительный анализ концептуальной плексности и грамматического числа в русском и английском языках

Аннотация

Цель исследования состоит в том, чтобы, во-первых, понятийно объяснить различия в грамматическом числе некоторых русских и английских слов, а во-вторых, на основе лингвистического эксперимента продемонстрировать, каким образом (если это возможно) грамматическое число в английском языке отличается от концептуальной плексности. Основной темой исследования является характер связи между концептуальной плексностью и тем, как она кодируется с помощью языка. Результаты исследования показали, что между концептуальной плексностью и грамматическим числом не существует идентичного соответствия, причем эта связь является двусторонней. Заимствования из классических языков влияют на дискурсивную практику и способ грамматического употребления множественного числа существительных в текстах. Количество функциональных частей, из которых состоит единица, влияет как на концептуальную плексность, так и на грамматическое число. Если большое количество отдельных частей предмета находится в непосредственной близости друг от друга (волосы, трава, пыль и т.д.), мозг воспринимает его как единое целое, что в языке кодируется грамматическим числом.

1. Introduction

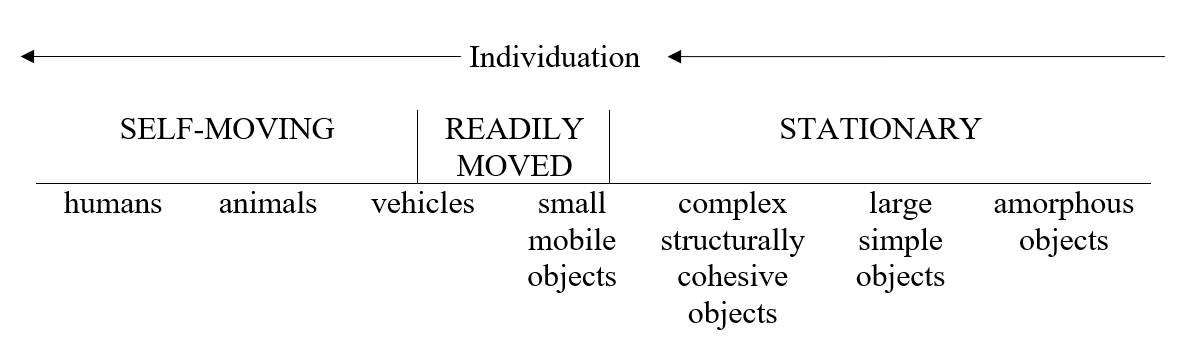

A strong point has been made by cognitive semanticists for different ways of conceptualizing plurality, which affects grammatical markings of singularity and plurality (, , , , ). The logical category of number “is based on the existence of quantitative characteristics of things and events. A human being first comprehends the number of things and objects and then tries to express them by means of languages” . The position according to which words’ grammatical plurality is directly linked to the way certain entities are conceptualized can be briefly summarized in the following way. Concrete objects and abstract phenomena are perceived either as individuable and therefore countable or as more or less unbounded homogeneous matter that is not individuable or countable, with these being two extremes on a continuum with some in-between cases:

While many entities are pre-individuated based on perceptual experience, individuation itself constitutes a continuum. For instance, animate entities, like inanimate entities, exhibit strong perceptual coherence. However, by virtue of remaining perceptually stable during motion, animate entities are more easily individuated. Conversely, amorphous objects, such as substances, are likely to be less easily individuated than discrete objects because they are less perceptually coherent .

Fig. 1 illustrates the degree of individuation of various entities, with humans, animals, vehicles and small mobile objects being individuated the most, and large simple and amorphous objects – the least.

Figure 1 - Degree of individuation of entities (after V. Evans, 2010)

[+b, –i] = individuals (a teapot, a mountain, a person)

[+b, +i] = groups (a committee, a team)

[–b, –i] = substances (mud, rice, water)

[–b, +i] = aggregates (teapots, cattle, committees)

The first thing to note about the classification is that perceptually groups, some substances (such as rice, flour, dust, but not water or mud) and aggregates that are grammatically unmarked for plurality (like cattle, for instance) are not unlike pluralized ‘individuals’: we perceive a committee and a team as consisting of many different individuals. Unlike a team or committee, however, entities like cattle seem to be unbounded, as one can easily add a couple of animals without destroying the integrity of the cattle. By contrast, a team and a committee seem to be more rigid in terms of their boundedness: they are, as a rule, more or less stable, and even if new members are added, it will arguably be a new team and another committee, while cattle (or even the cattle) will remain just that with the addition of new members. This is because human individuals as parts of teams or committees are cognitively more salient than animals as parts of a herd.

The main research problem is therefore the nature of the link between conceptual plexity and the way it is encoded by language. The aim of the research is twofold: first, to explain conceptually the differences in grammatical number of some Russian and English words; second, on the basis of linguistic experimentation, to demonstrate in what way (if any) grammatical number in English differs from conceptual plexity.

2. Research methods and principles

The main research methods are (1) a comparative grammatical and conceptual analysis and (2) linguistic experimentation. The research hypothesis is that there are multiple ways in which grammatical number and conceptual plexity are connected: in other words, conceptual multiplexity is not necessarily reduplicated in grammatical plurality and vice versa.

3. Cross-cultural conceptualization of number (Russian vs English)

To illustrate some differences in cross-cultural conceptualization of certain entities and to highlight how these result in grammatical markings of plurality, the following English-Russian pairs of nouns have been selected that are differently marked for plurality: woods – лес (леса), beetroot(s) – свёкла (свеклá), earnings – заработок (заработки) (But: savings – сбережения), money (monies) – деньги (деньга), cherries – вишня (вишни), plums – слива (сливы) (But: apricots – абрикосы); advice (advices) – совет (советы).

As is known, the Russian «лес» can be rendered as either ‘wood’ or ‘woods’, with both variants being quite appropriate grammatically and semantically. The very existence, however, of both singular and plural English counterparts goes to show that there are cross-cultural differences in the way one and the same entity is conceptualized. Unlike the Russian «лес», which is bounded, the English ‘woods’ is unbounded: it seems that native speakers perceive this entity as naturally sprawling without having any boundaries, it is accordingly can be likened to natural forces like the wind or rain, which are hard to restrain once they assert their presence. In Russian, this sense can also be accessed, but with the plurality marker: if the idea of vastness is to be conveyed, the lexeme «леса» is chosen. This, however, is stylistically and pragmatically marked, more restricted in usage and frequently occurs in the collocation «леса и поля». The absence of the plurality marker in the Russian neutral variant «лес» is explained by the fact that there are many artificial forest plantations, obviously conceptualized as bounded.

The Russian «свёкла» and its vernacular variant «свеклá» correspond to the English ‘beetroot’. The latter can be grammatically pluralized (beetroots), which means that members of this entity can be conceptualized as individuals or as aggregates. In Russian, however, it is categorized as a substance not unlike rice, and is typically not pluralized, as in the sentence «В продаже имеется свекла» (Cf.* «свеклы»). In the traditional Russian culture свёкла has played quite a significant role: it is the core ingredient in the first course bortsch. The leaves are also sometimes used as an ingredient in another traditional first course ‘okroshka’, as well as a nourishing food supplement for domestic animals. Given this and the relatively big size of свёкла, it would only seem logical that the members of the entity should be individuated and counted. This, however, does not seem to be true.

An interesting case to consider is the pair «earnings – заработок (заработки)». «Заработок» can be regarded as the pragmatically neutral counterpart of the English «earnings». «Заработки» cannot, however, be regarded as a translation equivalent of the English «earnings» or as an instantiation of a similar conceptualization of entities, although both are marked for grammatical plurality. A common component in their cognitive structure is that both may come from several sources, but then their common cognitive paths diverge. The English word «earnings» sounds quite prestigious and ‘manly’. Earnings are associated with bringing home the bacon, they are usually monthly or yearly and are regular. No tinge of specific social or affective meaning can be traced here. Not so with the Russian «заработки». First and foremost, they are not regular and the common collocation the word occurs in is «поехать на заработки», in which the noun is socially and pragmatically marked and encodes the following conceptual information: I need an additional source of income, as what I earn is not enough for me; or: I am collecting money towards some rather expensive purchase. Prototypically, that would also mean that the speaker works in a classless society, and it is almost impossible to earn more in their profession. In contemporary Russian society the word «заработки» still retains some of these connotations and is more readily associated not with city dwellers but with migrant workers and small rural areas, where many young people are unemployed. Contrariwise, the word «сбережения» sounds more prestigious and is associated with money saved for the rainy day. In English savings are more associated with one’s bank account(s), while in Russian сбережения might also be kept somewhere inside one’s dwelling. Savings and сбережения are gradually and intermittently added to and are therefore always conceptually pluralized. The words’ singularization would result in the noun form no longer denoting a material entity, but rather a process (сf. «сбережение», ‘saving’), which is part of both words’ original meaning. However, through the processes of metonymization, substantivization and pluralization the words acquired an entity-like conceptual and semantic structure.

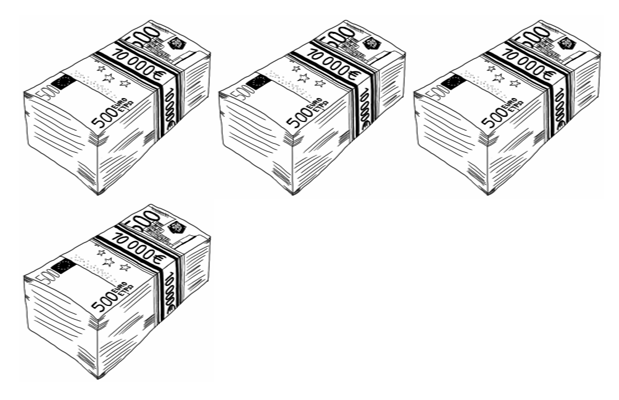

The word «money» is categorized as singular due to the fact that the entity is perceived as a substance with no boundary and no internal structure. If, however, reification takes place, the noun becomes conceptually and grammatically plural: in legal contexts, ‘moneys’ (or ‘monies’) means ‘sums of money’. In this case, discreet piles of money can be visualized, with the entity acquiring internal structure, although still having no boundary (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2 - Conceptualization of ‘moneys’ (‘monies’)

Another case of cross-cultural divergence is the names of some fruit, which is conceptualized as countable (having boundary and internal structure) in English and is more like a substance in Russian. This works for the nouns «вишня» and «слива». By metonymic transference, in Russian these are used as names of trees as well as their fruit, although the direction of transference is not clear. They can both be pluralized, but these pluralized variants sound somewhat old-fashioned and are associated with older generations of Russians. The stylistically neutral variant is singular – «вишня», «слива» (сf. «килограмм вишни/сливы» v.s. «килограмм вишен/слив» (#)). Here the hash tag is meant to point out the slightly old-fashioned and hence rarely heard structure in modern Russian. From the cultural relativity point of view, this can be explained by the fact that in traditional Russian horticulture, these types of fruit usually come in large, mass quantities, individual berries are not counted and rotten ones are discarded when they are culled. They are also quite evenly spread across Russia, unlike apricots, which are found only in the warmest parts of the country. The Russian word «абрикосы» has a different semantic structure, because the corresponding entity is conceptualized somewhat differently. In traditional Russian horticulture apricots have not been extensively cultivated due to the climatic limitations, therefore, they are rarer, with each apricot counted and appreciated. The fact that apricots are bigger than cherries may also play a role.

The entity behind the Russian noun «совет» is conceptualized as countable and consequently more like a concrete entity – a discreet piece of information that is supposed to help the recipient to solve some problem. In contrast, the English ‘advice’ is not pluralized in its neutral, every-day application. Pluralization of ‘advice’ becomes possible when reification takes place: it is no longer a piece of one’s mind that is given to the recipient, but quite a tangible, material piece of paper – a letter that informs the recipient of something, as in the example: We have just received the latest advices from our Paris correspondent.

Cultural salience of certain entities can also be gauged by establishing whether entities have special words for denoting a discreet member. All the concrete Russian nouns discussed above seem to have such a word, although some of them are more entrenched in the language than others. Because the referents of «вишня» and «слива» are objectively small, the words «вишенка» and «сливка» are used to denote discreet members of each fruit. Note that the words are diminutive, but not necessarily hypocoristic. The reverse seems to hold true for the Russian word «яблоко»: the addition of the suffix «-чко» results in hypocoristic reading, and not necessarily diminutive. Because a member of «абрикосы» is bigger than a cherry (though it’s approximately the same size as plums), the noun «абрикос» is used for a single category member, which is neither diminutive nor hypocoristic. A somewhat problematic case is the noun «клубника», which does not seem to have an optimal neutral name for a single berry: first, «клубника» can also be used with reference to a single berry («Дай мне одну клубнику»); second, «клубничка» might be used with reference to a whole mass of berries, and not necessary to a single berry, in which case it automatically receives hypocoristic interpretation (cf. «Клубничка в этом году славная уродилась»). In contradistinction, the Russian «картошечка» can only refer to a mass of potatoes, with «картофелина» serving as a name for individual members. If the diminutive suffix ‘-инк’ is added to the word («картофелинка»), then the reading is either hypocoristic or diminutive. The big size of cabbage resulted in a separate, partitive word for a single member of this class – «кочан» (or the dialectal «вилок») in Russian and a ‘head’ in English.

Although there are some cross-cultural variations, it seems that the smaller the size of certain fruit, vegetables and cereals, the less likely it is that nouns denoting fruit, vegetables and cereals will be pluralized, with parts of rice, millet, buckwheat, etc. being so small, that they are not ‘worthy’ of individuation either in Russian or in English: with the exception of the Russian «рисинка», a separate word is needed to refer to a single representative of the above entities – ‘a grain of’ in English and, somewhat less optimal, «зернышко» in Russian.

4. Conceptual vs grammatical plurality

Conceptual plurality can be roughly defined as thinking of an entity or its constituent parts in terms of two, several, much or many. Grammatical plurality is the possibility to linguistically refer to more than one instance of an entity, which is reflected in languages by special plurality markers – for the English language by (typically) adding ‘s’ to the end of words. Testing for a possible discrepancy between grammatical and conceptual plurality and not singularity is justified by the typically unmarked status of the singular, which “has zero form, while the marked plural has one more morpheme. From an experiential perspective, the singular is semantically unmarked since the prototypical speaker is a single person, not a chorus” .

Conceptual plurality may be coincidental with grammatical plurality: cf. dogs, fingers, toys. This is because it is possible to invoke more than one representative of each entity that fully preserves its integrity. Apparently, this is what R. Jackendoff had in mind when he used the term ‘boundedness’. Grammatical plurality may be at odds with conceptual representation, as in scales, tongs, scissors. These nouns, which refer to objects consisting of two or several parts and are always grammatically plural, are known as pluralia tantum. However, the entities referred to by these words are conceptualized as singular when only one representative is meant. The clash between conceptualization and grammatical representation requires a special word to be used when the entities are conceptually plural – typically, the word ‘pair’ is placed before the noun when the reference is to more than one instance (‘two pairs of scissors/scales/compasses’, etc.).

Conceptual plexity may partly diverge from the unmarked grammatical encoding of number in the so-called singularia tantum nouns, such as ‘hair’ and ‘grass’, which are unambiguously conceptualized as plural – thought of as more than one, and typically many. If isolated representatives are meant, then the word ‘hairs’ and ‘grasses’ are used to denote sparse hair and different types of grass, respectively. Another group is constituted by the entities referred to by such words as ‘data’, ‘paraphernalia’, ‘media’. While these are marked for grammatical plurality in the languages they were borrowed from (Greek or Latin), this marking is not entrenched in the English language and is not so salient for native speakers because it is marginal to the system of grammatical plurality in English. The result is that it has become acceptable to treat suchlike words as grammatically singular, indicated by the possibility of the singular concord – data is, media is (cf. ‘The 7/7 bombers left behind some data, but not much ’ . ‘Johnson’s data on developmental patterns for particular lexical items is compelling’ ). The non-systematic ways in which the word ‘data’ is used is evidenced in the following pair of sentences used one after another by the same author: while in the first the noun ‘data’ is singular, in the second it is plural:

Bacz (2000) provides a succinct discussion of this issue as far as Polish data goes. The Polish data pose a problem for any monolithic account of preposition and case because different prepositions relate to case in different ways .

Another variant of conceptual and grammatical discord is constituted by what we suggest calling ‘intra-grammatical clash’, when conceptually singular entities are redundantly marked for grammatical plurality, although the singular concord is typically used when only one representative is meant. These are entities referred to by the words ‘gallows’, ‘works’ (in the meaning of ‘factory’), ‘barracks’, ‘crossroads’, and the like. Table 1 sums up the possible range of relations between conceptual and grammatical plurality. The question mark accompanies entities whose conceptual representation is not unambiguous and is going to be tested in the experiment.

Table 1 - Relations between conceptual and grammatical plurality

Coincidental, no cognitive clash | toys, fingers, books, etc. |

Out of synch with each other | 1. Grammatically plural, conceptually singular when only one representative is intended – scissors, scales, tongs, etc. |

2. Grammatically singular, conceptually plural (singularia tantum) – hair, grass, rice, buckwheat, millet, beetroot etc. (?), furniture, etc. | |

3. Grammatically and conceptually unstable – could be either singular or plural – data (?), paraphernalia (?), media (?), etc. | |

4. Intra-grammatical clash – redundantly marked for plurality, singular concord is admissible. Conceptually singular when one representative is meant (pluralia tantum) – gallows (?), works (?), barracks (?), crossroads (?), etc. |

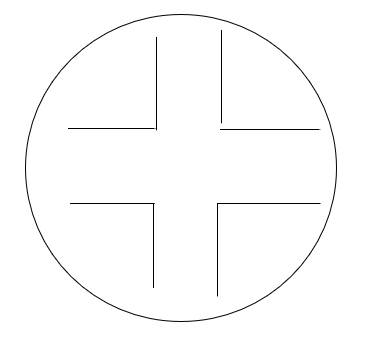

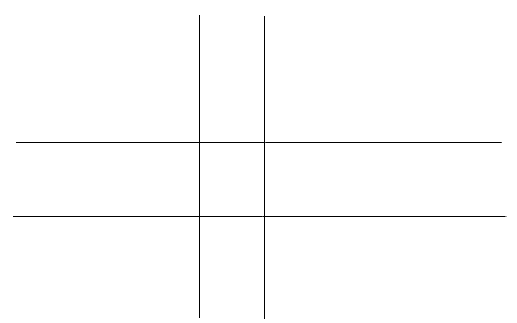

There are some problematic cases, marked in the table by a question mark. Whereas hair and furniture are indisputably conceptually plural – as in the classical sentences such as ‘She has long hair’, ‘There is no furniture in the room’, etc., because, obviously, not a single hair and not a single piece of furniture are implied – there are more complicated cases conceptually, with some words redundantly marked for grammatical plurality, such as ‘barracks’, ‘crossroads’ and, less apparently, ‘gallows’. The problem with ‘media’ and ‘data’ is that the words refer to abstract entities, therefore, it is not immediately apparent how they are conceptualized – as plural or singular. Finally, the problem with ‘barracks’ and ‘crossroads’ and to a lesser degree with ‘gallows’ is that although they are grammatically singular – as evidenced in the singular concord when a single entity is referred to – they could be conceptualized as plural on the following grounds: a barracks is a place where the military live, it is a collection of buildings divided into ‘compartments’, therefore the idea of plurality may be rather pronounced. The same pertains to a crossroads – although it could be thought of as a single entity where cars can move into four different directions, it could also be conceived of as two intersecting roads or four distinct roads. Fig. 3-5 sums up the conceptual representation of a crossroads:

Figure 3 - Crossroads as a single entity

Figure 4 - Crossroads as two intersecting roads

Figure 5 - Crossroads as four roads

Conceptual plexity of the gallows is also complicated. Provisionally, it seems that it tends to be conceptualized as singular rather than plural, because unlike in the case of a crossroads or a barracks, its parts are more proximal and its boundaries are more apparent, that is, it is perceived holistically: there are no visible compartments in it, nor does it consist of several functional parts, as in the case of the crossroads, where several (maximally four) functional parts are distinguishable. However, the fact that the contraption usually stands on two supports and that, historically, it was frequently used for multiple hangings, might contribute to its conceptualization as plural. The bipartite structure of the gallows is redolent of objects like scissors, scales, etc.

5. Experiment

To scientifically test for the possible discrepancy between conceptual plexity and grammatical plurality, a linguistic experiment was conducted for which the following nouns were selected: scissors, scales, swings, data, media, paraphernalia, hair, grass, rice, buckwheat, millet, beetroot, furniture, gallows, works, barracks, crossroads, water, dust. These nouns were selected because to a greater or lesser degree the conceptual representation of the entities they refer to seem to be out of sync with the linguistic representation of their grammatical plurality. Some nouns which clearly refer to several individuated instances of an entity are not marked for plurality (grass, hair, furniture, etc.). Others, which refer to a single occurrence of an entity, are, conversely, marked for plurality: scissors, scales. Even if the argument that these entities consist of two parts is invoked, which seems to account for the words’ plurality, examples can be found that contradict words like scissors and scales: the word ‘bra’, for instance, refers to an object made of two distinct parts, and yet it is unmarked for plurality when referring to a single object. The same concerns a see-saw (aka a teeter), which has two functional parts (two seats), yet both words for the entity – ‘see-saw’ and ‘teeter’ – are singular when referring to a single representative.

To test conceptual representation of some problematic entities, a questionnaire was devised that was filled in by Martin Hewings – one of the leading authorities on English Grammar and academic English. The participant was required to allocate suggested words into one of the four groups. Below is the questionnaire used in the procedure (Table 2):

Table 2 - The questionnaire offered to a proficient native speaker in order to test the conceptual representation of entities that contain the idea of plexity

Some riders are in order as regards the suggested options and procedure. First, as in all test formats, it was made clear to the participant that any questions about the test – its procedure, tasks, etc. – could be clarified at his earliest convenience. Second, it is not obligatory that all the groups should be filled in: while all the possible alternatives have been spelled out, it remains to be seen how many of them are conceptually viable. For this reason, specific examples for each group were not provided, because that might have programmed the respondent to answer in specific ways, which would skew the research results. Third, it was suspected that some of the selected words, namely ‘water’ and ‘dust’ – may stay outside the suggested classification, therefore the ‘Your comments’ section was added so that the respondent could spell out problematic cases, if any.

Below is the table (Table 3) filled in by Martin Hewings.

Table 3 - Answers to the questionnaire

Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | Group 5 |

scissors scales gallows barracks | hair (refers to strands of hair as entities) rice (grains) buckwheat (grains) millet (grains) beetroot (roots) furniture (items) dust (particles) | paraphernalia | crossroads | data media |

Your comments (for indicating whether you had difficulty in allocating some of the words, optional): swings and works don’t seem to fit in any of the groups: grammatically plural, but referring to several entities water doesn’t fit either: grammatically singular but referring to a single entity | ||||

6. Results

After running the experiment, some of the expectations held before its onset were confirmed. However, some of the findings held surprises. As was hypothesized, hair, furniture, dust and all the cereals are conceptualized as plural, as well as beetroot, although the word for this entity lacks the plurality marker. This stands in partial contradiction to the groups singled out by R. Jackendoff, who claims that rice and suchlike entities do not have an internal structure. According to the findings, they do. Unlike dust, which is conceptualized as plural, water is regarded as conceptually singular, apparently, because it does not consist of easily distinguishable particles. The words we were particularly interested in – data and media – revealed a curious feature: the fact that they have started to be used as grammatically singular seems to have affected their conceptualization: both words have been placed into the group which admits of singular conceptualization. Unlike data and media, the word paraphernalia can be grammatically singular or plural, but always refers to a group of things. Our expectation, however, was that all the three words would be placed into one and the same group, because of their common origin (Greek via Latin) and grammatical properties (plurality). Although many grammars state that gallows and barracks can be used with the indefinite article and are thus grammatically singular when referring to a single entity, the respondent indicates that they are grammatically plural even when referring to a single entity. It seems, therefore, that the fact that they consist of several parts (two in the case of gallows and many compartments in the case of barracks) at least partially affects their linguistic representation. Although it was expected that gallows, barracks and crossroads would be placed into the same group, the participant states that unlike gallows and barracks, crossroads can be grammatically singular when it refers to a single entity. It seems, therefore, that a crossroads tends to be conceptualized as a single entity, which corresponds to the encircled cross in the figure above. Somewhat unexpectedly, swings and works were grouped together as being grammatically plural and referring to several entities. Traditional grammars indicate that ‘swings’ can be used in the singular form (a) ‘swing’, unlike the word ‘works’ (in the meaning of a ‘plant’), which can’t be used with the indefinite article and is always grammatically plural. Although the noun ‘swings’ has a singular counterpart, it is more often used in the plural, which is probably explained by the fact that modern playgrounds are equipped with a row of swings, with typically a pair of swings attached to a single support. Therefore, it is more typical to say, ‘The children are playing on the swings’ rather than ‘The children are playing on a/the swing’. This is reflected in dictionaries: pictorial illustrations usually contain a row of swings (Fig. 4). Dictionary examples give preference to the plural noun – ‘swings’.

Figure 6 - Typical swings

Note: picture source: https://www.hendersonplay.com/product-category/swings/arch-swings/

7. Discussion

The findings of the experiment turned out to be mixed. Although the words ‘gallows’, ‘barracks’, ‘paraphernalia’, ‘data’ and ‘media’ are allocated to different groups, they all seem to confirm the thesis that the way we talk (or represent words graphically) influences the way we think: the fact that the three Greek nouns do not have the typical English plurality marker ‘-s’, facilitates their transition to grammatical and, partially, conceptual singularity. Conversely, ‘gallows’, ‘barracks’ and ‘works’, because they retain the plurality marker ‘-s’, are predominantly thought of as grammatically and, partly, conceptually plural. In Group 2, neither language nor cognition seems to be having an impact on each other, instead they seem to be completely independent of each other. All the words are not marked for grammatical plurality and yet the entities behind them are conceptualized as plural; nor does the fact that the entities are conceptualized as plural seem to have a bearing on their linguistic representation – in no way can these nouns be used with ‘-s’ (with the exception of ‘beetroot’ and ‘hair’, the latter with a change in meaning) or have a plural concord (hair, millet, rice, beetroot, etc. # are). Interestingly, the word ‘beetroot’ is in stark contrast to the conceptualization of the vegetable it names – as indicated by M. Hewings, real roots (many) can be represented in language as ‘root’ (one part of ‘beetroot’, hence it is singular).

Cross-linguistic differences and mistakes of L2 learners seem to demonstrate that the way we think influences the way we talk, rather than the other way round. Beginning Russian learners of English (and sometimes even intermediate to advanced) tend to say ‘#My hair were/are…’, which goes to show that it is much easier for them to learn that ‘hair’ is used without the plurality marker than to use the singular concord. It seems that in order to use the singular concord, learners should first start thinking of hair as singular. However, because of the influence of Russian (in which «волосы» is plural), this is problematic, and so learners have to drill and remember the concord somewhat mechanically and artificially. Also of interest are pronouns that can substitute for nouns like ‘hair’ and ‘furniture’ anaphorically or cataphorically (e.g. ‘it’ or ‘they’): just like the concord, they are hard to internalize. Russian students of English are prone to say ‘#They (hair) were/are dirty/clean’ rather than ‘It was/is dirty/clean’. Intermediate and advanced learners are less likely to say ‘hairs’, ‘monies’ or ‘furnitures’ because they are not exposed to these rare or grammatically wrong variants.

8. Conclusion

The present research proved that there is no one-to-one correspondence between conceptual plexity and grammatical number. The direction of the link turned out to be two-way. Borrowings from classical languages affect the discursive practice and the way nouns are used in texts; the number of functional parts seems to affect both conceptual plexity and grammatical number; when a big number of small exemplars of an entity are in close proximity to each other (hair, grass, etc.), the brain seems to perceive it as a single whole, which is encoded in language by grammatical singularity. Some of the limitations of the research are that only one native speaker took part in the experiment. However, he is a credible authority on English grammar, and therefore his comments are invaluable in shedding light on why some substances and entities are conceptualized as either singular or plural and in what way it affects their grammatical number. Naturally, subsequent research into conceptual and grammatical plexity could be augmented by data from naive native speakers, i.e. those who are not engaged with English grammar professionally. Another limitation is that the experiment was conducted on the basis of English. In subsequent studies, it would be of benefit to carry out a comparative experiment, selecting examples from English and Russian.