SOME TYPICAL FEATURES OF HONG KONG ENGLISH PROSODY AS MARKERS OF NATIONAL IDENTITY

SOME TYPICAL FEATURES OF HONG KONG ENGLISH PROSODY AS MARKERS OF NATIONAL IDENTITY

Abstract

The study focuses on some of the most typical prosodic features of Hong Kong English, the variety which emerged in the former British colony under the substrate influence of the speaker’s native language – Cantonese. The acquired prosodic features are treated in the current study as markers of the speaker’s national identity in spoken speech.

The typical features of Hong Kong English prosody are identified by means of acoustic analysis of rhythmic and melodic organization of spontaneous speech of 20 Hong Kong English speakers. At the conclusion of the study, the author gives a prosodic characteristic of the variety, viewed as a medium for expressing the speaker’s national identity. It is believed that the findings of the research will advance the knowledge of the understudied Hong Kong English phonology, as well as reduce risks of communicative failures in cross-cultural discourse due to its divergences from Standard English pronunciation.

1. Introduction

Hong Kong English (hereinafter referred to as “HKE”) is a direct consequence of the British colonial era. According to historical sources, British control over Hong Kong officially lasted from 1842 to 1997, up to the year when the territory was handed over back to China under the Sino-British Joint Declaration and acquired the status of the Special Administrative Region (SAR) of the People's Republic of China. Throughout the colonial period, English was the official language of the territory, penetrating into such formal settings as governance, legal system, education, business and professional sectors [13, P. 4, 104–107]. The exposure of ordinary Hong Kong people to English through free nine-year compulsory education, which was introduced in the 1970s, brought about mass bilingualism in Hong Kong. After the 1997 Handover, English did not go away from the territory, and more importantly, it has continued to be used in many domains of daily life [10], [13, P. 107–112]. Its solid position has been upheld not only by its status as a global lingua franca, but also by the prominent international standing of Hong Kong itself, which is a large seaport, as well as the world’s 3rd most significant financial and trading centre [7], seating numerous headquarters of transnational corporations. Alongside Chinese (Cantonese as a spoken dialect), English remains the official language of the territory, and thanks to high academic standards and bilingual or entirely English medium instruction in some of Hong Kong’s schools and universities, 3,750,000 out of 7,501,000 residents are English users (2019 census) [6].

Currently, English in Hong Kong holds socio-economic value. It is regarded as a means for receiving higher education, getting a better job, boosting career prospects and earning potential, or, to put it otherwise, attaining higher social status in the long run. Because of its long-term benefits, English has ceased to be identified with colonial culture or as the colonizer’s language, the more so, it has acquired a prestigious status in Hong Kong society. What is more important, it has assimilated into Hong Kong culture [9], becoming its deep-rooted and essential component, and a medium for transmitting Hong Kong identity. In linguistic terms, English, being nativized by Hong Kongers, has developed a distinctive localized variety with its own identifiable linguistic features [4] that set it apart from other English varieties and start to serve as speech markers in national identification.

However, not following British or American standards, the specific features of HKE are potentially able to hinder the auditory comprehension process in cross-cultural interactions, with the major obstacles arising on the phonetic level of language. The problems of auditory comprehension of HKE speakers have become especially sharp these days as in the contemporary globalized world HKE enjoys broad usage functioning in such discourse domains as business, trade, tourism, science, technology, education, and multimedia. But despite the emergence of the new variety of English and its tangible presence in cross-cultural contacts, it has been insufficiently studied by linguists, as over a long period of time it has been categorized as a sub-standard or a deficient form of English. HKE phonetic features also remain left out of English teaching process, most notably out of English listening practice. It is well known that in teaching English as a foreign language, listening comprehension practice is mainly limited to the development of learners’ ability to listen to and comprehend native varieties of English, particularly its British and American pronunciation standards, while HKE and other non-native English varieties are often missed out. Meanwhile, the importance of raising students’ ability to comprehend non-native English speakers, including HKE speakers, cannot be overestimated due to the national specifics of their phonetic systems.

Owing to the lack of experience in perceiving and comprehending HKE accent, unfamiliarity with its most typical phonetic features, the acquired norms of British or American pronunciation standard and their correlation with HKE pronunciation forms, English learners may experience difficulties in understanding spoken speech in HKE. It means that during the act of communication in a cross-cultural setting, the phonetic features of HKE, generated by the deviations from Standard English pronunciation, may cause misunderstanding or even result in communication breakdown.

Considering that all the major elements of the phonetic structure of language (speech segments, word stress, sentence stress, rhythm, and melody) are able to affect the auditory comprehension process, the way the listener perceives and interprets the information content of an utterance is largely determined by how well the listener is aware of the speaker’s pronunciation type. For this reason, in order to adequately understand HKE speakers, it seems worthwhile to get familiar with those phonetic features that are associated with a typical HKE accent and make up its distinct characteristic.

In this regard, the paper progresses to compiling the phonetic portrait of HKE at the prosodic level due to the fact that prosody is one of the most noticeable markers of the speaker’s personal, social and national identity in spoken speech [5, P. 261]. What is more, HKE prosody, especially its melodic constituent, lacks thorough and comprehensive research. The existing studies of the HKE variety on rhythm, stress, and melody, are quite patchy and incomplete and do not give a full picture of the HKE prosodic system. It is anticipated that the corpus-based accountof HKE prosody provided below will make a contribution to the existing knowledge, as well as encourage further investigation.

2. Research methods and principles

At this point, it seems appropriate to clarify that HKE is currently at an early stage of nativization [12]. It still has a long way to go before it evolves into a mature variety with established norms. Obviously, the current immaturity of the variety results in instability and variability of local pronunciation forms, dependent on the speaker’s English proficiency level, the degree of mother tongue interference, the speaker’s choice between native-speaker norms of English and local nativized forms, communicative situation and other extralinguistic factors. In view of that fact, the prosodic features, highlighted in the current paper as the prosodic markers of HKE speakers’ national identity, indicate the most shared and stable trends, spotted in the speech corpus of 20 HKE subjects. Furthermore, as the typical features of the variety are a result of substratum transfer from Cantonese to English, in the most notable cases, the prosodic features of HKE are described in reference to the prosodic properties of the substrate language Cantonese, as well as in comparison with the base language – British English, the variety from which HKE developed.

To identify the most typical features of HKE prosody, a speech corpus consisting of the recordings of 10 male and 10 female subjects was compiled. The informants were chosen as HKE speakers on account of their linguistic and educational background, and made a more or less homogeneous group. All the subjects, aged from 18 to 60 or over, classify themselves as Hong Kongers, with Hong Kong being the place of their birth and residence, speak Cantonese as their mother tongue, have a high proficiency level of English, completed a higher education qualification or are undergraduates, and come from middle or upper-middle class families. By occupation, the HKE group is mostly made up of university teachers, professors, scientists, lawyers, doctors, legislators, politicians and government officials. For comparative purposes, a speech corpus comprising the recordings of 20 (10 men and 10 women) native British English (BE) speakers formed a reference group. The speech data selected for analysis were collected from the original interviews with the subjects, recorded on RTHK Radio 3 [11] and BBC Radio 4 [2]. The HKE corpus, the same as the BE corpus, included spontaneous speech and were composed of the subjects’ answers to an interviewer’s questions. The speech data analysed was approximately 5 minutes long for each subject. The total length of the HKE corpus was 102 min 14 sec, and that of the BE corpus was 99 min 02 sec [1, P. 83], which made the size of the analysed material sufficient.

With an integrated approach adopted, the study involved the following research methods: theoretical analysis, sociophonetic analysis, proper phonetic analysis (perceptual speech assessment and acoustic instrumental method), comparative analysis, and statistical tools for data processing and interpretation. For the acoustic analysis of speech samples, the computer software package Praat (version 6.2.14) of free access [3] was employed. During the analysis, the following tasks were assigned: to reveal the most shared rhythmic characteristics of the subjects’ spontaneous speech; to establish the subjects’ averaged pitch level and range; to determine the fundamental frequency (F0) peak and its alignment with the syllable structure in the intonational phrase (IP); to study the F0 contour in the head, on the nucleus and the tail of the IP, and to identify the inventory of nuclear tones and their shapes.

To explore the properties of speech rhythm in HKE, a mini-speech corpus (the first two minutes of the recording of each speaker from the HKE and BE groups) was selected, and the durations of each stressed and unstressed syllable were measured (in milliseconds, ms) and compared. Then the mean values for the durations of the stressed and unstressed syllables and their duration ratios were calculated for each of the two groups. To accomplish the other tasks of the study, the mean values for the pitch range (in semitones, ST) and level (in Hertz, Hz) were obtained for each female and male subject; the F0 peak of an IP was identified and measured, and the correlation between the F0, duration and intensity in nuclear tones was found in each utterance.

3. Main results

We start the discussion of the results by establishing the length of IPs. IPs in the speech data under analysis vary in number of stressed syllables and include from one to seven stressed syllables per phrase. However, the vast majority of utterances (74.6%) tend to break in short IPs comprising – in order of frequency – two (30.5%), three (22.7%) or only one (21.4%) stressed syllable(s) per phrase [1, P. 104]. A separate IP can contain a single polysyllabic, disyllabic or monosyllabic word, which could be either a content or function word, and which receives emphasis through not only temporal but also melodic accentuation. Parts of a sentence that can form a separate IP are as follows: a subject, including a personal pronoun subject; a verb, including an auxiliary and “to be”; an object; an adverbial of place or time, including one at the end of an utterance. For example: →I | was ˈborn | in ˈHong ̷ Kong || We →fought →for | the imˈprovement | in the ˈteaching of | ↓Chinese | and ˈEnglish →languages || We →go to ˈten ̷ markets | to com→pare | ↓prices | →of a | ↓basket →of | ˈfifteen ↓items ||

On the rhythmic continuum, HKE is more inclined to syllable-timed patterns than Standard British English, which is a stress-timed language by traditional definition [5, P. 261]. Indeed, the lack of reduced vowels in unstressed positions is key to perceiving HKE rhythm as syllable-timed. The tendency of HKE speakers not to use a reduced vowel, such as a schwa, in monosyllabic function words and unstressed syllables of some content words results in insignificant difference between the durations of stressed and unstressed syllables. By contrast, in BE stressed and unstressed syllables considerably differ in duration. In our findings, the ratio value for the durations of stressed vs. unstressed syllables in the corpus of the HKE speakers is 1.2:1, while in the corpus of the BE speakers it is 1.7:1 [1, P. 113]. It was established that the HKE speakers showed smaller differences in the syllable durations in stressed and unstressed positions by lengthening the duration of unstressed syllables. The difference between HKE and BE data was found as statistically significant. The signs of syllable-timed rhythm in HKE are a result of a possible transfer of rhythmic properties from Cantonese, whose rhythm is syllable-timed rather than stress-timed, with the vast majority of syllables containing a full vowel and each syllable receiving emphasis to more or less the same degree [13, P. 36]. The absence or minimum vowel reduction in unstressed syllables and the tendency for breaking utterances into short IPs are among the factors that contribute to auditory impressions of HKE rhythm as abrupt and staccato.

The frequent occurrence of stressed monosyllabic function words is another specific feature of the rhythmic organization found in the speech of the HKE subjects. Such monosyllabic function words as personal and possessive pronouns, auxiliaries, prepositions, and conjunctions, which would rarely be stressed in BE, are commonly emphasized in HKE despite the fact that these words do not carry the key information or are not contrastive in any way. In our study, the HKE speakers stressed monosyllabic function words in 22.3% of observations [1, P. 116], even though the words were not the focus of the utterance, nor was their emphasis rhythmically required. In the BE corpus monosyllabic function words received prominence in 8.9% of observations. Emphasis fell on such words either before a short pause made for thought or due to rhythmic requirements. It is important to note that prominence on monosyllabic function words in the corpus of the HKE subjects was realized not only by means of increased intensity and / or duration, but, in some occurrences, also by means of pitch change from low to high. The high frequency of stressed monosyllabic function words in HKE could be explained by the transfer of some prosodic features from Cantonese, in which each syllable carries a tone for meaning differentiation and, consequently, receives some degree of phonetic prominence [8].

In regard to the melodic organization of HKE, it has been found that the heads of IPs in the HKE data feature a high number of enclitic and proclitic feet, in which unstressed syllables realize at a lower pitch as opposed to the preceding stressed syllable. On average, this type of foot accounts for 41.5% among all the feet in the heads of the IPs [1, P. 132]. The tendency to lower the intonation contour on unstressed syllables was manifested in the conversational data of each HKE subject, though the frequency of individual usage of this type of foot varied from subject to subject (from 15.38 to 77.80%). It was not characteristic of the BE subjects, in whose data unstressed syllables in the foot tended to remain at the same pitch level as the preceding stressed syllable (74.8% of observations). The difference in the number of these two different types of foot between the HKE and BE groups was identified as being statistically significant. Moreover, a F0 decrease on the post-stressed syllable in the foot in the HKE corpus was quite noticeable. In our study, the pitch movement was on average by 4.9 ST downward in the speech corpus of the Hong Kong female subjects and by 5.4 ST in the corpus of the Hong Kong male subjects, which meant a step down to a lower pitch level of the speaker’s range. It resulted in the formation of large intervals between the F0 peaks of the stressed and unstressed syllables in the foot. The tendency to considerably lower the F0 contour on the post-stressed syllable can be described as a characteristic feature of HKE melody. In other words, in the head of an IP of the HKE variety, the F0 tends to significantly go down on unstressed syllables and up on stressed syllables of succeeding feet. The F0 contour in the head can be realized either as a glide from the stressed to the unstressed syllable or as a sequence of almost level steps or tones which step down and then up to each other. Possible variants of the F0 movement in the head of an IP of the HKE variety are provided in figure 1:

Figure 1 - F0 movement in the head of an IP of the HKE variety

Note: line for stressed syllable; dot for unstressed syllable

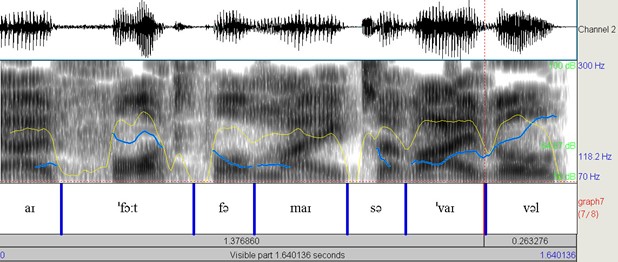

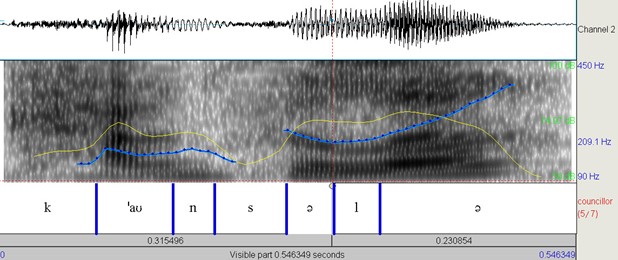

The typical pitch-to-pitch pattern of the intonation contour in the head of the IP I ˈfought for my sur ̷ vival produced by a HKE male speaker can be clearly observed in figure 2:

Figure 2 - F0 contour in the utterance produced by a HKE male speaker

Note: blue curve indicates F0; yellow curve indicates intensity

The pitch-to-pitch pattern of the intonation contour in the head of an IP can also be attributed to substratum interference of the register properties of the Cantonese tonal system in which tonemes, being an indispensable suprasegmental element of each syllable, are contrastive to each other in pitch height with a descending melodic tendency within a minimal rhythmic unit [8].

The paper moves on to a discussion of the inventory of nuclear tones and their shapes in HKE.

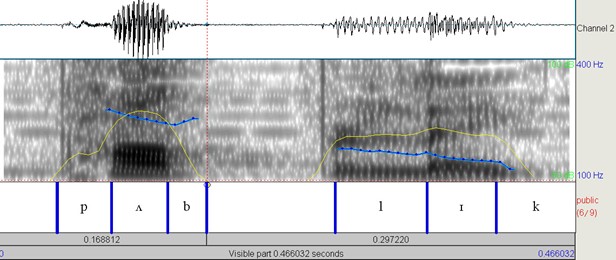

With respect to the falling tones found in the speech corpus of the subjects, the specific feature of HKE melody showed in the presence of falls, which are realized by means of a major pitch change in the tail in relation to the preceding nuclear syllable. The pitch change leads to the formation of large F0 intervals (up to 10 ST) between the nucleus and the tail of any segment composition [1, P. 146–148]. As in the head, the intonation contour can be realized either as a gradual glide from one pitch level to another or as an abrupt step down from the stressed to the unstressed syllable. This characteristic pattern of the intonation contour of nuclear falling tones distinguishes HKE from BE, in which this kind of falling configurations is not typical, and is also attributable to substratum interference of Cantonese. In figure 3, a large interval (4.9 ST) between the F0 peak of the nuclear syllable (230.8 Hz) and that of the tail (173.2 Hz) is evident:

Figure 3 - Falling contour in the utterance produced by a HKE female speaker

Note: blue curve indicates F0; yellow curve indicates intensity

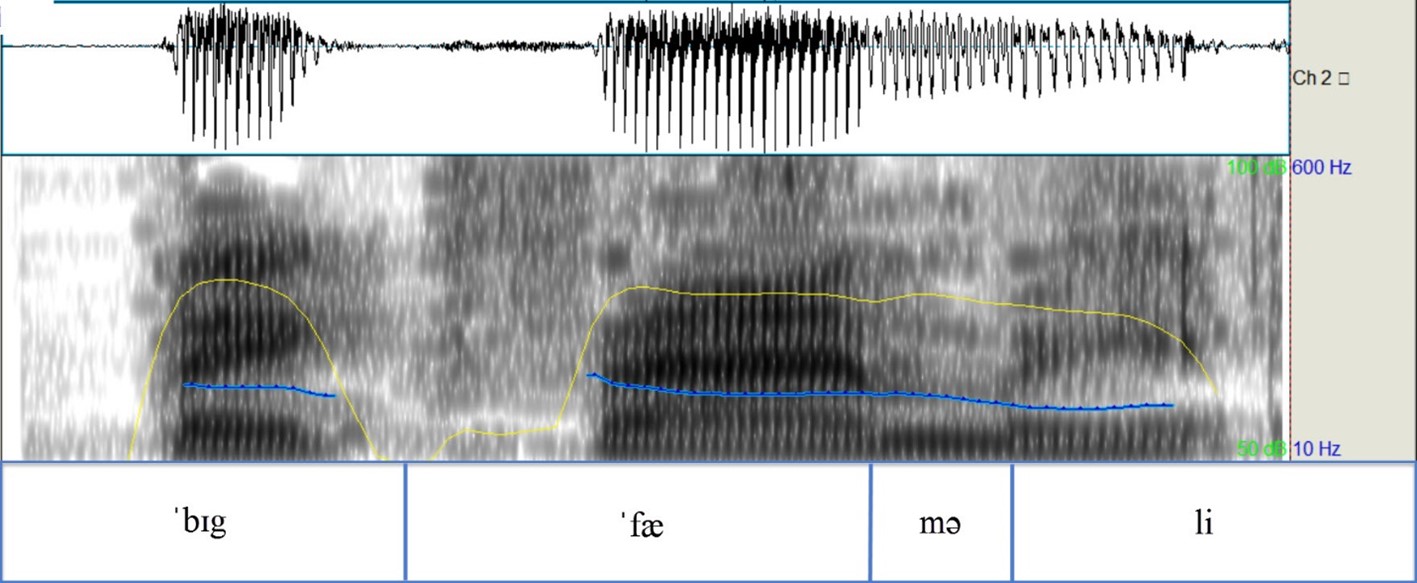

Another specific feature of KHE melody manifested itself in the tendency to sustained plateaus, which may end the falling movement in the nucleus or tail or even form right after the start of the falling movement within the nuclear syllable. Plateaus may be lengthy in duration and cover the domain of a diphthong, long or short vowel, or sonorant. The formation of plateaus makes HKE falls extended, smooth and narrow with a small degree of slope. This is the reason why in more than half of cases the falling configurations in the KHE speech corpus tended to be almost flat with a slope of 0.168 to 0.528 Hz/ms [1, P. 148–150, 153]. The tendency to sustained and prolonged glides of a narrow range can also be considered as a specific feature of HKE melody. For example purposes, in figure 4, one can observe a gradual falling movement on the three-syllable word family. The falling contour starts at the F0 peak of 176.6 Hz and goes down to 140.2 Hz, moving on to an extended plateau which covers the rest of the stressed vowel [æ]. Interestingly, the duration of the plateau (93 ms) exceeds the duration of the preceding falling movement (69 ms). On the unstressed syllables, the intonation contour continues to fall gradually to the F0 min of 110.4 Hz. The overall range of the falling movement is 8 ST, and its slope is only 0.220 Hz/ms.

Figure 4 - Falling contour in the utterance produced by a HKE female speaker

Note: blue curve indicates F0; yellow curve indicates intensity

Apart from the falling configurations mentioned above, delayed falls (with the F0 peak aligned with a post-stressed syllable and the falling pitch movement occurring in the tail), falls with initial rise, and falls with the continuous falling pitch movement through the tail across polysyllabic words have also been found in the HKE speech corpus.

Relating to rise-falls, first, it is noteworthy to point out that the HKE speech corpus has featured a fair number of rising-falling contours expressing neutral attitudes. The vast presence of neutral rise-falls makes HKE distinguishable from BE, where the Rise-Fall has emotional colouring. Second, as in realization of the falling contours, a considerable part of the rising-falling configurations has been marked by a plateau which may be stretched in duration and either finish the falling contour, or form in between the rising and falling segments, or even precede the rising movement. In the latter case, the plateau is implemented on a stressed long vowel, diphthong, nasal consonant, or approximant. Third, besides the regular shape of rising-falling tones, in which the falling segment exceeds the rising segment in range and duration, and the F0 peak is aligned with the nucleus, there are also arc-shaped rising-falling configurations of either wide or narrow range, in which the rising and falling intervals are almost identical due to their relatively equal ranges, slopes and durations. This shape is not typical of the BE Rise-Fall.

Concerning rising nuclear tones, it must be noted that in the HKE speech corpus rises have been encountered not only in non-final but also in final IPs. All the more so, the rising tones occurring in final IPs outnumber those in non-final IPs – 50.3% vs 49.7% [1, P. 161]. The most frequent rising configuration is the one that starts with a rather lengthy flat segment which covers the beginning of a monosyllabic word or the entire stressed syllable of a di- / polysyllabic word. Then, at the end of the word, the flat pitch contour transforms into a rise of a wide range (up to 15 ST) and often reaches the top of the speaker’s pitch range. This feature has especially been observed in the speech corpus of the female speakers. In terms of slope, the mean value for the whole HKE group is high – 1.137 Hz/ms (std=0.654 Hz/ms); in other words, in 68% of occurrences the slope values vary from 0.483 to 1.791 Hz/ms [1, P. 155–156]. The tendency for abrupt and steep rising configurations of a wide range sets HKE apart from BE, in whose tonal system rising tones are more gradual and smoother and rarely reach the top of the speaker’s range. The specifics of this type of rising contours in HKE are most likely to be attributable to the transfer of the properties of high level and rising tones in the Cantonese tonal system [8]. The graph below illustrates a rising nuclear tone, which goes across the speaker’s entire pitch range up to its highest pitch level in the utterance (see figure 5).

Figure 5 - Configuration of the Rise produced by a HKE female speaker

Note: blue curve for F0; yellow curve for intensity

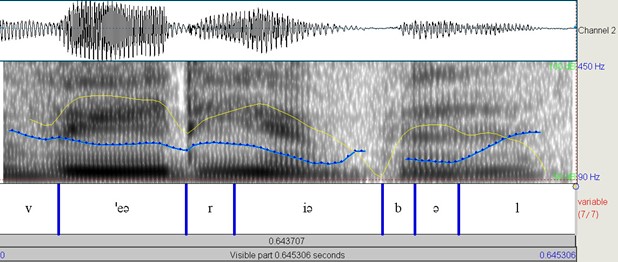

Similar to rising tones, falling-rising tones in HKE can be found not only in non-final IPs (to express non-finality, incompleteness or uncertainty, or mark parenthesis, adverbials of place and time at the beginning of an utterance) but also in final IPs. An important feature of the falling-rising contours in the HKE speech corpus has shown in the tendency for a high ending of the rising pitch movement. In other words, the endpoint of the rising segment may reach or even exceed the pitch height of the start point of the falling segment. This type of shape of the Fall-Rise differentiates HKE from BE standard, in which the falling movement is more prominent in pitch range, slope, or length, and the F0 peak is always concentrated on its start point. Figure 6 serves as an example of a common shape of the Fall-Rise in HKE.

Figure 6 - Configuration of the Fall-Rise produced by a HKE female speaker

Note: blue curve for F0; yellow curve for intensity

Lastly, the HKE corpus has also been characterized by the high frequency of level tones, occurring in both non-final and final IPs (18.7% of occurrences). If the level tone is implemented on a di- or polysyllabic foot in anon-final IP, the stressed syllable is featured by the maximum intensity and the last unstressed syllable – by the maximum duration. In final IPs, level tones, which have a flat (static) F0 contour, are perceptually identified as falling tones, which happens due to an abrupt and rapid decrease in intensity.

4. Conclusion

HKE is an evolving English variety, which has developed a number of prosodic features which can serve as means of national identification. The prosodic features that can be deemed as the markers of HKE identity are as follows:

- a tendency to syllable-timed rhythm;

- short IPs which can be composed of only one word, including a monosyllabic function word, which becomes prominent not only through an increase in duration and intensity but also through tonal changes;

- a pitch-to-pitch pattern of the F0 contour in the head of an IP, achieved through a F0 decrease on the unstressed syllable in the foot and a subsequent F0 increase on the stressed syllable of the next foot, which results in the formation of considerable intervals between the F0 peaks of stressed and unstressed syllables;

- falling nuclear tones which are realized through pitch change in the unstressed syllable in relation to the preceding stressed one with the formation of large intervals between the F0 peaks of the syllables of any segment composition;

- falling nuclear tones which are realized as gradually descending glides with low values of slope;

- a large number of rising-falling nuclear tones, neutral in meaning;

- steep and abrupt rising nuclear tones of a wide range at the end of a mono- / polysyllabic word, frequently reaching the top of the speaker’s pitch range;

- falling-rising nuclear tones, tending to end the rising movement at the same pitch height as the start of the falling movement or even higher than that;

- a tendency to form a plateau on diphthongs, long and short vowels, and approximants within the nucleus or tail during the realization of a nuclear tone of any type.

It is viewed that the prosodic characteristics singled out above have the potential to lay the foundation for the future prosodic standard of HKE, which will be of cultural value to its speakers and serve as a medium for expressing their national identity.