СООТНОШЕНИЕ ИДИОМАТИЧНОСТИ И ЭВФЕМИСТИЧЕСКОГО ПОТЕНЦИАЛА ФРАЗЕОЛОГИЧЕСКИХ ЕДИНИЦ В АНГЛИЙСКОМ ЯЗЫКЕ (НА ПРИМЕРЕ НОМИНАТИВНОЙ ГРУППЫ «БЕДНЫЕ СТРАНЫ»)

Аннотация

Introduction

A euphemism is one of the oldest language tools originating in ancient taboos. With the development of civilization and society euphemistic units acquire new functions. Using euphemisms, speakers seek to avoid a direct mention of something awkward or unpleasant, thereby saving the speaker’s "face", the "face" of the interlocutor or a third party [8].

Being an unstable part of the lexical fund, euphemistic units often lose their potential and disappear from the language, acquiring a negative shade of meaning as a result. The “euphemistic potential” in the research is meant to be the ability of a lexical unit "to soften a strong reaction to something unpleasant, terrible and reproaching" [3, P. 20].

In this study we have set ourselves the task to trace the connection between the idiomaticity degree of phraseological euphemisms pertaining to the nominative group "Poor countries" and their euphemistic potential.

Method

The methodology applied in the research is based on A. A. El'garov’s lexical correlation theory, which states that the correlation types are defined by the multifaceted interaction of a phraseological unit (PU) with its lexical environment. The idiomaticity degree was determined according to the criteria developed by A. N. Baranov and D. O. Dobrovol'skij: a) the reinterpretation of a lexical unit, b) its transparency, or absence of motivation [2].

The phraseological euphemisms selected for the analysis were taken from R. W. Holder’s dictionary of euphemisms [15]. The contexts under analysis range from the early 20th century to the present day, which enables us to trace the evolution of the lexical units in question.

We took into account possible linguistic and extralinguistic peculiarities (i. e. frequency, polysemy degree, communicative situations), which could have an indirect influence on the euphemistic potential of phraseological units [3], [6].

Discussion

Most scientists, including N. N. Amosova [1], G. V. Kolshansky [4], A. V. Kunin [5] and A. A. Elgarov [7], argue that a sufficient context is required to carry out a coherent and exhaustive study of PUs, which is predetermined by their complexity. While in the case of a lexeme, one meaning out of many is actualized in a particular context, a PU is not as polysemantic and thus the context serves to foreground certain aspects of its meaning.

The process of a PU realisation in speech involves the correlation of its semantics with the value of other linguistic elements, united by the same thematic and situational relevance. A. A. Elgarov states that the meaning of a PU can be amplified when it enters a semantic relationship with its lexical correlates. The linguist suggests classifying the semantic relations into the following types: synonymy, antonymy, hyponymic relations, reference to the same lexical-semantic field, associative relations in the context. [7, С. 10-11].

Results

Having analysed contexts that span a hundred years, we observed the following tendencies.

The noun ‘country’ has a high valency index, since it may collocate with a number of lexical items (developing, disadvantaged, industrialising, in transition, underdeveloped, etc.) to form free word combinations. The denotational and connotation meaning, however, may vary depending on the evaluative and referential components of the adjectives.

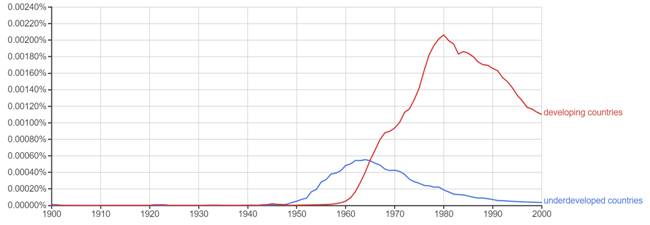

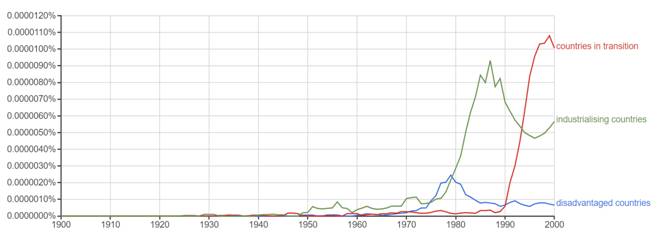

As it can be seen in Fig. 1–2, the frequency of the items peaked in the following chronological order: underdeveloped countries (peaked in the 1960s) > disadvantaged countries (peaked in the late 1970s) > developing countries (peaked in the early 1980s) > industrializing countries (peaked in the late 1980s) > countries in transition (peaked in the 2000s).

Fig. 1 – Frequency chart of the PUs ‘underdeveloped countries’ and ‘developing countries’

Fig. 2 – Frequency chart of the PUs ‘disadvantaged countries’, ‘developing countries’ and ‘countries in transition’

The study finds that all the highlighted PUs with the element ‘country’ have been able to perform a euphemistic function.

Let us consider the euphemistic potential of each lexical item separately.

The seme ‘development, progress’ in developing country immediately triggers positive associations in the reader’s mind. The expression seeks to airbrush reality, presenting the turbulent post-liberation period in a more positive light: (1961) “In any new and developing country, leaders play a dominant role. This has been particularly true of the leaders in the African states, so many of which have acquired both independence and international stature in the past three years, and even during the past months” [20]. The article fails to mention the economic and political instability, indebtedness and social unrest that the newly-liberated African countries had to face at that time. Such perception is further enhanced by lexical units with a positive connotation, i. e. independence and international stature:

The PU a country in transition is often resorted to in order to downplay the gravity of the current situation, since a transitional period is accompanied by instability and uncertainty. It comes as no surprise that the peak was registered in the 1990s. Following the breakup of the Soviet Union and the Soviet Bloc, the former members underwent major economic and political transformations. We should note, however, that the term is not limited in its application and may be used to refer to any country that is changing politically or economically: (2006) “Tony Blair: ‘We have to recognise Indonesia has been a country in transition. What people recognise is how far that has moved since the current president came into office’” [9]. The lexical correlates how far and has moved actualize the seme ‘movement, progress’ thereby showing the process of transition as a change for the better.

The PU an industrializing country defined by R. W. Holder as ‘a poor and relatively undeveloped state’ [15] displays a high euphemistic potential: the seme ‘progress, development in industry’ places an emphasis on the key area of development and its ongoing character. The phrases cut off from the rest of the world, communication with the outside world was illegal form an antonymic correlation with ‘industrialising country’ thus demonstrating a marked contrast between life in Iraq and life in Iran. The semantic opposition adds to the positive connotation of the PU: (2005) “The Iraqi capital was cut off entirely from the rest of the world; … communication with the outside world was not just controlled, as it is in Iran, but illegal. Tehran, on the other hand, looks and feels like the capital of a rapidly industrialising country” [21].

The study shows that older euphemisms can develop slightly negative connotations, however the semantic opposition between poor and economically advanced countries is not clear enough to speak about semantic pejoration. The distinct negative emotive charge can be traced in the PUs containing the elements ‘underdeveloped’ and ‘disadvantaged’. It could have developed from the ideas behind the prefix under- (‘lower in status’; ‘insufficiently’, ‘incompletely’) and dis- (‘showing opposite or negative’) respectively [19].

The frequency of ‘underdeveloped’ peaked in the 1960s but declined within the following decades. The clearly negative connotation of the expression accounts for the decrease. The semantic opposition is illustrated in the following example with the poor countries being involved in agricultural activities and the economically advanced being the consumers: (1959) “Secretary of State Christian A. Herter called on other prosperous industrial nations today to give more help in the task of aiding underdeveloped countries” [14]. The concept also includes the idea of inequality: the writer compares underdeveloped countries to the needy and thereby arrives at the conclusion that inequality is a broad notion and it may reflect the unequal distribution of economic resources among countries.

Today the term is often applied to criticise advanced countries by comparing them to underdeveloped regions: (2018) “It [the school] was not suitably upgraded and the conditions resemble those seen in documentaries about old-fashioned orphanages in underdeveloped countries” [18]. The attributes the most chaotic, old-fashioned enhance the negative evaluative component and add a note of contempt and deprecation.

The PU a disadvantaged country possesses a rather vague meaning, as it may be unclear what exactly is meant by ‘disadvantaged’: what particular domains of life it concerns, what events or processes are behind the current economic situation. Reinforced by the immediate context (depletion of natural resources, heavy indebtedness, unstable prices, etc.), a heavy emotive charge of the adjective ‘disadvantaged’ can sometimes produce a negative connotation: (1997) “The present situation is particularly serious in economically disadvantaged countries burdened by depletion of natural resources, heavy indebtedness, unstable commodity prices and unfavourable trading systems.” [17]

The expression developing often appears alongside the terms ‘developed countries’, ‘industrialized countries’ thus establishing a partial antonymic correlation. The concept of a developing country comprises the idea of scant financial resources and a dire need for foreign aid: (2013) “Gender equality? The WEF ranks us behind Nicaragua and Lesotho. Investment by business? The Economist thinks we are struggling to keep up with Mali. Let me put it more broadly, Britain is a rich country accruing many of the stereotypical bad habits of a developing country” [10]. The author shames Britain by likening it to a developing country in terms of gender equality and investment – areas in which developed countries are expected to set an example.

The PU an industrializing country describes a region where the shift from agricultural to industrial labour is under way, but it faces numerous challenges, such as indebtedness, shortages of resources, lower demand for certain skills leading to a higher unemployment rate. The recorded lexical correlates emergency plan and energy shortages indicate that the PU may acquire an occasional contextually bound negative connotation: (2016) “In 2005, the government drew up an emergency coal production plan to curb the effects of huge, impending energy shortages in the rapidly industrialising country” [12].

The idiom banana republic, unlike the ‘x + country’ collocations, admits of no structural modifications. The PU ‘banana republic’ is used to refer to “a small state that is politically unstable as a result of the domination of its economy by a single export controlled by foreign capital” [19]. The term came into existence in the early 19th century after it was coined by the American writer O. Henry to describe a fictional country in his collection of short stories ‘Cabbages and Kings’ [23].

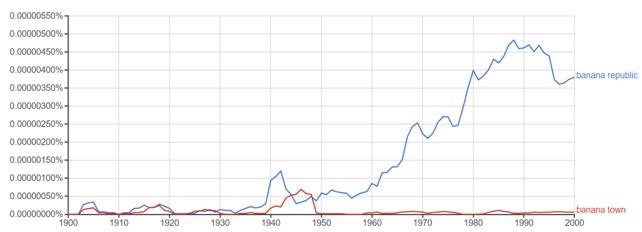

From 1900s to 1930s the term was loosely applied to agricultural states in Latin America in connection with 1) their main economic activities or 2) the disadvantaged conditions people were forced to live in (pestilential, malaria). The first group of contexts are surprisingly devoid of any negative connotation with lexical correlates suggesting an overall positive attitude (train loads of green fruit, chief article of export, area under cultivation, we fully appreciated it). It is worth mentioning that the cohesion between the elements ‘banana’ and ‘republic’ was weaker, in particular we have observed instances of ‘banana town’, ‘coffee republic’ in reference to Latin American countries. As it is seen in Fig. 4, the PUs ‘banana republic’ and ‘banana town’ had the same distribution in the 1940-50s, with the latter plummeting in the 1950s (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 – Frequency chart of the PUs ‘banana republic’ and ‘banana town’

Over the course of time the expression acquired new shades of meaning. The lexical correlates bring out the semes of instability (peace and order problems, precarious, in jeopardy, instability), backwardness (semi-savage), dependence and servitude (would have been less advanced economically, dabbled in local affairs, submissive nations), usurpation of power (history of military dictatorships, the heavy hand of a dictator).

As far as the connotational meaning is concerned, the PU carries a noticeably heavier emotive charge than in earlier contexts: “Well, what could those little banana republics do, even if they had entered the war.” [11, P. 14]. In the example, by resorting to the demonstrative pronoun those, the speaker expresses his contempt for ‘banana republics’, further enhanced by the adjective little – ‘relatively unimportant or trivial’ [19], while the conjunction even if implies the speaker’s skepticism about their military potential. The following example makes reference to the related phenomena (banana fingers and banana boys), which proves that the concept of the fruit itself has been subject to semantic pejoration: “… we have all grown up to be contemptuous of bananas. We talk of 'banana republics' and 'banana fingers' and 'banana boys'” [22].

Within the last three decades the PU has seen a slight departure from its original denotational meaning while the connotational meaning has maintained its emotive potential. The expression ‘banana republic’ is less often used to refer to Latin American countries and their economic activities. The semes of political and economic instability (about to implode, weight of its compounding debt), non-democratic regime (military leader, refused to allow the democratically-elected government to take office; tyrannical, cruel hypocrisy) and political fraud (fraud which would disgrace a 'banana republic') have come to the fore thus changing the referent. As the negative connotation has become entrenched in the minds of the English speaking community, the expression, due to its evaluative component, has gained traction and is now often used by journalists to criticize advanced countries (the USA, the UK, Germany) and faults in their political and socio-economic systems by comparing them to backward states: (2013) “There are few acts more tyrannical than keeping innocent men captive. It is no secret that this has been happening at Guantanamo and that it is an intentional political choice. This dishonors America. It is a cruel hypocrisy that, ultimately, makes us no better than a banana republic” [16].

Conclusion

Upon examination, the selected contexts allow us to make the conclusion that the phraseological units with high valency and transparent semantic motivation (underdeveloped / industrialising etc. country) tend to maintain their euphemistic potential for a long time period, even though the degree of reproducibility is in inverse proportion to the euphemistic property of a word combination. Although the semantic opposition between poor and economically advanced countries might be present in the context, the PUs under analysis may point to an overall positive trend. Considering frequency rate from the diachronic perspective, the euphemism ‘a developing country’ has remained at the top of the list for the last sixty years.

The term ‘banana republic’ has acquired new shades of meaning throughout its usage (political and economic instability, backwardness, dependence and servitude, usurpation of power and political fraud). The contextual analysis proves the expression was prone to a slight semantic change, as soon as it became a ready-made reproduction.

Список литературы

Амосова Н. Н. Основы английской фразеологии / Н. Н. Амосова. – Л., 1989. – 208 с.

Баранов А. Н. Идиоматичность и идиомы / А. Н. Баранов, Д. О. Добровольский // Вопросы языкознания. - 1996. – № 5. – С. 51-64.

Кацев А. М. Эвфемистический потенциал и его реализация в речи. / А. М. Кацев // Некоторые проблемы слова и предложения в современном английском языке: респ. сб. / Горьк. гос. пед. ин-т А. М. Горького. – Горький, 1976. – С. 19-35.

Колшанский Г. В. Контекстная семантика / Г. В. Колшанский. – М.: Издательство «Наука», 1980. – 154 с.

Кунин А. В. Курс фразеологии современного английского языка: учеб. для ин-тов и фак-тов иностр. Языков / А. В. Кунин. – М.: Высш. шк., 1986. – 336 с.

Порохницкая Л. В. Концептуальные основания эвфемии в языке (на материале английского, немецкого, французского, испанского и итальянского языков): автореф. дисс. ... д. филол. н. / Л. В. Порохницкая. – М., 2014. – 46 с.

Эльгаров А. А. Условия и лексические средства актуализации семантики фразеологизмов (на материале номинативных фразеологических единиц современного английского языка): автореф. дисс. … канд. филол. наук / А. А. Эльгаров. – М., 1983. – 23 с.

Allan K. Forbidden words. Taboo and Censoring of Language / K. Allan, K. Burridge. – Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006. – 314 p.

Branigan T. Blair criticised over Jakarta talks / T. Branigan // The Guardian [Electronic resource]. – 2006. – Mar 30. – URL: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2006/mar/30/politics.indonesia (accessed: 21.05.2018)

Chakrabortty A. Let’s admit it: Britain is now a developing country / A. Chakrabortty // The Guardian [Electronic resource]. – 2013. – Dec 09. – URL: http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/dec/09/britain-now-developing-country-foodbanks-growth?CMP=fb_gu (accessed: 21.05.2018)

Commercial America. – V. 39. – No 2. – Philadelphia: Philadelphia Commercial Museum, 1942. – 85 p.

Doshi V. Coal India accused of bulldozing human rights amid production boom / V. Doshi // The Guardian [Electronic resource]. – 2016. – Jul 13. – URL: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2016/jul/13/coal-india-accused-of-bulldozing-human-rights-mining-operations-amid-production-boom-amnesty-international (accessed: 21.05.2018)

Google Ngram Viewer [Electronic resource]. – URL: https://books.google.com/ngrams (accessed: 21.05.2018)

Herter Asks Foreign Aid Help. // Corsicana Daily Sun. – 1959. – Nov 17. [Electronic resource]. – URL: https://www.newspapers.com/newspage/ 12647142/ (accessed: 21.05.2018)

Holder R.W. How Not to Say What You Mean: A Dictionary of Euphemisms / R.W. Holder. – Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003. – 528 p.

Horsey D. Permanent imprisonment at Guantanamo betrays American values / D. Horsey // Los Angeles Times. – 2013. – May 07. [Electronic resource] – URL: http://www.latimes.com/opinion/topoftheticket/la-na-tt-guantanamo-20130506-story.html (accessed 21.05.2018)

Keckes S. Global Maritime Programmes and Organisations: An Overview / S. Keckes. – Maritime Institute of Malasya, 1997 – 211 p.

Kelleher O. Cork special school compared to ‘old-fashioned orphanage’ / O. Kelleher // The Irish Times. – 2018. – Apr 19. [Electronic resource]. – URL: https://www.irishtimes.com/news/education/cork-special-school-compared-to-old-fashioned-orphanage-1.3478061 (accessed: 21.05.2018)

Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English. – 3d ed. Harlow – Essex: Longman Group, Ltd., 1997. – 1680 p.

Melady T. S. New Men At the Top / T. S. Melady // Profiles of African leaders. – 1961. – Feb 26. – New York: The Macmillan Company. – 186 pp. [Electronic resource] – URL: https://www.nytimes.com/1961/02/26/archives/new-men-at-the-top-profiles-of-african-leaders-by-thomas-patrick.html (accessed: 21.05.2018)

Omaar R. Another country / R. Omaar // The Guardian [Electronic resource]. – 2005. – Apr 01. – URL: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2005/apr/01/iran.features11 (accessed: 21.05.2018)

Scott J. V. P. S. Again / J. V. P. S. Scott. – Cape Town: D. Nelson, 1975. – 128 p.

Where did banana republics get their name? // The Economist [Electronic resource]. – 2013. – Nov 21. – URL: https://www.economist.com/the-economist-explains/2013/11/21/where-did-banana-republics-get-their-name (accessed: 21.05.2018)