РИТОРИЧЕСКАЯ СТРУКТУРА ИССЛЕДОВАТЕЛЬСКОЙ СТАТЬИ ПО СТОМАТОЛОГИИ

Аннотация

INTRODUCTION

Dentistry has established itself as a valuable and recognized profession worldwide, and research in dentistry has become highly important not only to the professionals in dentistry but also to society. The scientific community in dentistry, that is dentists, academic staff, scientists and students, has increased to the same extent as the number of dentistry journals and conferences.

Today we are witnessing an overwhelming Anglophone supremacy in research articles in the field of dentistry published by such international journals as The Journal of Dentistry, British Dental Journal, The Journal of the American Dental Association, European Journal of Dentistry to mention a few. Moreover, there has been a rapid growth of e-journals, which broadens the access to published research as well as affects the schematic structure of research articles (henceforth RAs).

There is no doubt that the English language has become the world’s principal language of research. Flowerdew [8, p. 301] mentions a number of factors that have contributed to this phenomenon: first, the internationalization of higher education and research; second, the establishment of league tables, in which publications in high impact journals are important indicators of high standards, and alike. As a result, publishing manuscripts in high-impact-factor journals, which are usually in the English language, is required for promotion in countries worldwide.

Research articles written for the disciplinary discourse community in dentistry, viewed as an internal community within the institution and/or beyond having specialized expertise in a particular field, contribute to the body of knowledge in dentistry and are ‘richly persuasive rather than flatly expository’ [9, p. 218].

Gunnarsson [4,p. 61] contends that ‘language and discourse are essential elements in the construction of medical science, in profession-building and in the shaping of a medical scientific community.’ The RA genre plays an important role in this process, as it not only constructs scientific knowledge and the role of scientist in society, but also contributes to social networking among medical scientific community all over the world.

Writing about the history of the medical article genre, Gunnarsson [4, p. 64] claims that ‘the medical article genre has become a within-science genre’, which means that the RA has emerged as a purely scientific internal genre addressed exclusively to the members of the discourse community, that is scientists and expert readers in dentistry, ‘without having to bother about a growing gap between the lay public and the experts’ (ibid.).

Thus, the goal of this study is to explore the genre of research article in dentistry in order to deepen the understanding of this professional genre. It aims at offering a theoretically grounded insight into the rhetorical structuring of the RA, which is of relevance to the discourse community in dentistry and beyond.

THE CONCEPT OF GENRE

Nowadays the concept genre embraces the predictable and recurring academic, professional and other text types that are used in a range of contexts. The most seminal definition of a genre has been proposed by Swales [10, p. 120], which claims that a genre comprises a class of communicative events, the members of which share some set of communicative purposes. These purposes are recognized by the expert members of the parent discourse community, and thereby constitute the rationale for the genre. This rationale shapes the schematic structure of the discourse and influences and constraints choice of content and style. If all high probability expectations are realized, the exemplar will be viewed as prototypical by the parent discourse community.

From this definition, it is obvious that an important aspect of the genre identification is a communicative event, in which two parties, that is, the writer and the reader engage in communication through the text. The parties share the understanding of the communicative purpose, which helps them distinguish one genre from another. The communicative purpose is the most important factor in genre identification because any major changes in it will give a different genre, but minor changes will help identify sub-genres, that is, a sub-type of a genre or a part-genre, that is, a section of a full genre (Bhatia, 1998: 45). The definition above also suggests that genres have a schematic structure, and the parties of the communicative event draw on this structure for constructing and construing the genre.

Similarly, Tribble (1996) and Hyland (2002) hold that a genre is a structured and conventionalized communicative event, and the members of the discourse community recognize the conventionalized internal structures of the genres. Moreover, Gunnarsson [4, p. 65] contends that ‘a robust scientific community reveals itself in firm genre conventions: in more homogeneous texts and also in explicit indications of group affiliation’.

Although genres are typically associated with recurring rhetorical contexts and are identified on the basis of a shared set of communicative purposes with constraints on allowable contributions in the use of lexico-grammatical forms, they are not static. Language users might vary the optional generic conventions in order to achieve their communicative purposes; however, they should follow mandatory structural patterns and lexico-grammatical features of specific genres which define their limits in order to ensure the pragmatic success of the genre in the appropriate context.

Genres are based on text-external, non-linguistic criteria, that is, the communicative purpose of the specialist community and the intended audience. In order to achieve specific goals of the genres, their discourse is constructed in several moves, that is, functional units fulfilling a coherent communicative function in the genre relating ‘both to the writers purpose and to the content that s/he wishes to communicate’(Dudley-Evans and St John, 1998:89) and steps, that is, sub-sets of the move that realize specific communicative functions, based on internal, linguistic characteristics.

The genre analysis of the schematic structure of genres provides insightful information for writing the RA genre in dentistry.

THE RESEARCH ARTICLE GENRE

Analysing the structure of medical RAs in Sweden from a diachronic perspective, Gunnarsson [4, p. 65] concluded that the titles of the headings used to structure the RA have shifted from the ones relating to the content of the RA to its structure, that is, Material, Methods, Results, Discussion and Conclusions, which confirms general scientific tendencies as well as ‘reflects a more homogeneous organization of the texts’. Gunnarsson [4, p. 66] argues that the medical RA has become established as a genre, which is an indicator of a growing medical discourse community. Also, for the dentistry scientific discourse community, published RAs are important markers of group membership.

Typical RAs form the so-called IMRaD structure, that is, the Introduction, Methods, Results and Discussion [3, p. 156-157]. Each of these four moves has a communicative purpose. The Introduction, moving from general topic-related issues to the particular research question/hypothesis, aims at providing the rationale for the RA as well as attracting the readers’ interest. The Methods section, being the narrowest part of the RA, describes the methodology, materials and research procedure. The Results section describes the findings, and the Discussion section provides ‘an increasingly generalized account of what has been learnt in the study’ (ibid.).

Ferguson offers the structure of the medical research article [8, p. 260]:

Introduction Move 1 Presenting background information;

Move 2 Reviewing related research (including limitations);

Move 3 Presenting new research;

Methods Move 4 Describing data collection procedure;

Move 5 Describing experimental procedures;

Move 6 Describing data analysis procedures;

Results Move 7 Indicating consistent observation;

Move 8 Indicating non - consistent observation;

Discussion Move 9 Highlighting overall research outcome;

Move 10 Explaining specific research outcomes;

Move 11 Stating research conclusions.

Having reviewed the openly available RAs in the British Dental Journal, it can be concluded that the RA in dentistry also tends to exhibit homogeneity in terms of the schematic structure, that is, the RAs are structured as follows: the Abstract, Background, Methods, Results, and Discussion. This indicates a strengthening of the RA genre conventions in dentistry. However, it is advisable to check the relevant publisher or journal before starting to write the RA, as they may have particular guidelines which should be followed.

The Abstract as a part-genre provides a description or a concise factual summary of the RA. Its importance has increased with the emergence of online databases, which offer free access only to abstracts but not RAs. The schematic structure of the Abstract is a carrier of disciplinary discourse community’s assumptions as to its form, and due to the ‘vastly increased size of the medical discourse community’ [8, p. 248] and its keen interest to publish their RAs, researchers must meet the discourse community’s expectations and structure their abstracts appropriately.

Swales [10, p. 181] contends that the RA abstracts follow the IMRAD pattern and points to five typical moves, that is, the Introduction, Methods, Results and Discussion, each move having a specific communicative purpose.

The Journal of Dentistry(Online) requests that the Abstract is presented under explicit subheadings: the Objectives, Methods, Results, and Conclusions.The British Dental Journal (BDJ) (Online) says that the Abstract should be structured under the following explicit headings: the Objective, Design, Setting, Subjects (materials) and methods, Interventions, Main outcome measures, Results, and Conclusion(s):

Objective: The abstract should begin with a precise statement of why the study was done, usually in one sentence. It should be possible to make a connection between the conclusion and the objective.

Design: A few words describing the type of study — for example, 'double blind trial', 'prospective random control trial', 'retrospective analysis', 'open study', and whether the study was single or multi-centre.

Setting: To assist readers to assess the applicability of the study to their own circumstances this paragraph should state whether the setting was the community, a university department, a hospital, or general practice. The country and year of the study should be given.

Subjects (materials) and methods: This should state whether and how subjects were selected and from what population. This will give the reader an idea of the generalisability of the results.

Interventions: This should include a description of any intervention. Generic names of drugs are preferred but trade names may be given as well in case there is some difference in the formulation from country to country.

Main outcome measures: Methods by which patients were assessed or the success of experiments judged should be mentioned, and those that may be unfamiliar to readers should be described. The outcome that was sought should be stated.

Results: The main results should be given, including the number, gender and age of the subjects, together with a note of the fate of exclusions and withdrawals. Numerical results should be stated as mean (SD) or mean (SEM) in the case of normally distributed data, and median (range or interquartile) if the data are skewed; 95% confidence intervals (CI) and the level of significance of differences should be indicated. If the differences in the main outcome measures between two (or more) groups are not significantly different the 95% CI for the difference should be given and any clinical inference stated.

Conclusion(s): Only those conclusions supported by the data that are presented should be given, followed by a short statement on the clinical applications of the results, if any, bearing in mind the limitations implicit in the study — for example, size of sample, number of withdrawals, or length of follow-up. (BDJ: Online)

The communicative function of the Introduction is to show the relevance of a particular study by placing it in the context of the previous research. A disciplinary discourse community may affect the way introductions are structured, though.

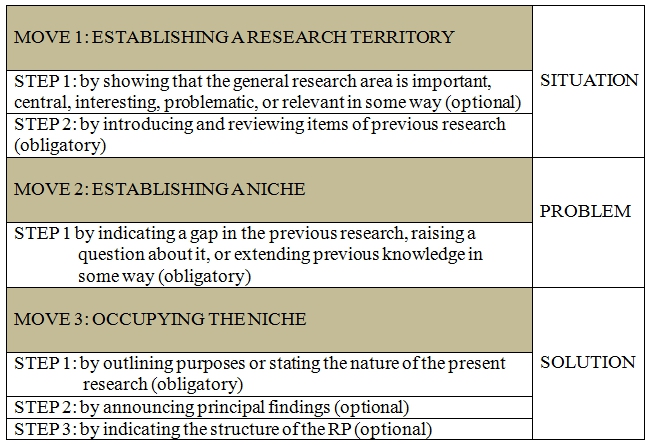

In Swales’ CARS model, the communicative function of Move 1 is to introduce the research field by showing that the particular research area is relevant, interesting or problematic in some way and by introducing items of previous research in the field. Move 2aims at establishing a niche by indicating a gap in the previous research, raising a question about it, counter-claiming, and/or extending previous knowledge in some way. The purpose of Move 3 is to occupy the niche by outlining purposes or stating the nature of the present research, and/or indicating the structure of the RA. Thus, here the writer states the significance of the research problem, indicates the research method used and the population of the research, followed by the outline of the RA.

Figure 1 CARS Model for Article Introductions (adapted from Swales, 1990)

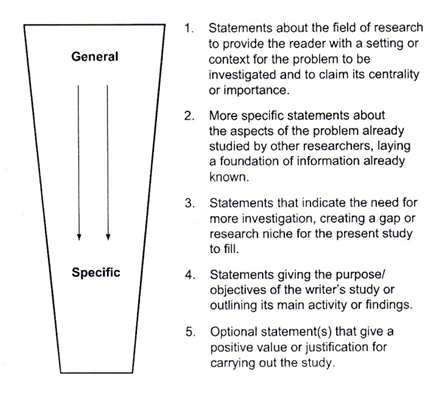

Figure 2 below emphasizes the structuring of the introduction: from more general statements to more specific ones.

Figure 2 Research article introduction: structure (Cargill and O’Connor, 2009)

The Journal of Dentistry sets the guidelines for the structure of the Introduction. It ‘must be presented in a structured format, covering the following subjects, although not under subheadings: succinct statements of the issue in question, and the essence of existing knowledge and understanding pertinent to the issue. In keeping with the house style of Journal of Dentistry, the final paragraph of the introduction should clearly state the aims and/or objective of the work being reported. Where appropriate, a hypothesis (e.g. null or a priori) should then be stated’ (Online).

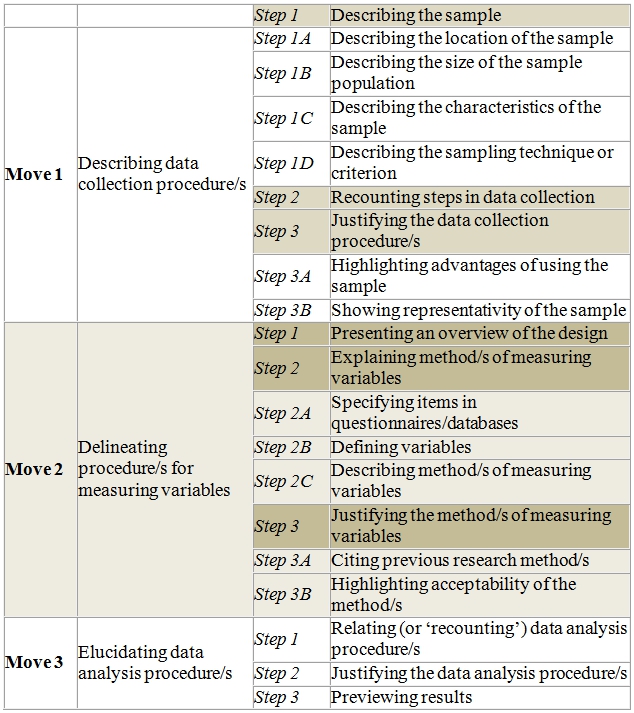

In the Methods section of the RA, scientists inform the reader about the research methods used in the study, give an account of how data were collected, what the procedure for the experiment or any other research method was, and how the data analysis was conducted. The Methods section should be clear and detailed enough for another researcher in the field to replicate the study and reproduce the results. The Methods section is generally structured in three rhetorical moves: (1) describing data collection procedures, (2) delineating procedures for measuring variables, and (3) elucidating data analysis procedures. Figure 3 below provides a detailed account for structuring the Methods section [7]. Each of the rhetorical moves is broken into more detailed steps.

Figure 3 Rhetorical structure of the Method section (Lim, 2006)

The Results section Bottom of Formpresents, describes and comments on the most important findings of the study. It typically 1) highlights the important findings; 2) locates the figure(s) or table(s) where the results can be found; and 3) comments on (but does not discuss) the results [2, p. 31].

As it can be seen, the Results section is likely to consist of tables and figures, which must be mentioned in the main body of the article, but scientists do not have to repeat in words all the results from the tables and figures, as commentary is expected only on the significant data shown. A summary statement usually identifies the table or figure and indicates its content, which is followed by statements pointing out and describing the significant data. More elaborate commentary on the results is normally restricted to the Discussion section.

In general, it is not uncommon for the Results section to be combined with the Discussion section under the heading: Results and Discussion.

Bottom of Form The Discussion section in the RA is probably the most complex section in terms of its elements. As there is usually more than one result, the Discussion section is often structured into a series of discussion cycles. The research questions posed in the Introduction should be answered, and the results with published data should be compared objectively. Their limitations should be discussed and the main findings emphasized. Contrary findings should be considered and only methodologically sound evidence should be used. At the end of the Discussion section or in a separate section, major conclusions should be drawn, and the practical significance of the study should be emphasized.

Bottom of Form

CONCLUSIONS

The pre-eminence of the English language as the lingua franca of scholarly publications has resulted in the Anglicization of the RA among the dentistry scientific community. This and the increasing use of the Internet as a means of scientific communication have led to the homogenization of the RA genre, as it is recognizable and sufficiently standardised. At the same time, the generic integrity of the research article genre should be viewed as dynamic and flexible.

The genre analysis is a helpful analytical tool, and the published studies on the rhetorical structuring of the RA genre are useful to dentistry professionals, students and scientists. It is recommended that RA writers familiarize themselves with the prototypical schematic structure of the genre and its part-genres. However, the expectations of the particular publisher or journal should be studied before manuscript submission, as they may be subject to the disciplinary variation and even variation across journals.

A further research could be undertaken in order to study the lexico-grammatical resources used to structure the rhetorical moves of the RA in dentistry. The present study can be of use to the dentistry professionals, as well as to applied linguists, as it provides insightful information for academic writing practice.

Список литературы

British Dental Journal. [Electronic resource] URL: http://www.nature.com/bdj/authors/guidelines/ research.html (Accessed 26.06.2016).

Cargill M. Writing Scientific Research Articles Strategy and Steps / M. Cargill, P. O’Connor. – Pondicherry: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

Feak C.B. Academic Writing for Graduate Students. Essential Tasks and Skills / C.B. Feak, J.M.Swales. – Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1994.

Gunnarsson B.-L. Professional Discourse. – London, New York: Continuum, 2009.

Hyland K. Teaching and Researching Writing. – London: Longman, 2002.

Journal of Dentistry. [Electronic resource] URL: http://www.journals.elsevier.com/journal-of-dentistry (Accessed 26.06.2016).

Lim J. Method sections of management research articles: A pedagogically motivated qualitative study // English for Specific Purposes. – 2006. – vol. 25. – № 3. – Pp. 282-309.

Paltridge B. The Handbook of English for Specific Purposes / B. Paltridge, S. Starfield. – Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013.

Swales J. Research genres. Exploration and Applications. – Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Swales J. Genre Analysis. – Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.