КОНЦЕПТ СВОБОДЫ В РУССКОЙ И КИТАЙСКОЙ ЛИНГВОКУЛЬТУРАХ: СРАВНИТЕЛЬНОЕ ЛИНГВОКУЛЬТУРОЛОГИЧЕСКОЕ ИССЛЕДОВАНИЕ

КОНЦЕПТ СВОБОДЫ В РУССКОЙ И КИТАЙСКОЙ ЛИНГВОКУЛЬТУРАХ: СРАВНИТЕЛЬНОЕ ЛИНГВОКУЛЬТУРОЛОГИЧЕСКОЕ ИССЛЕДОВАНИЕ

Аннотация

Статья посвящена исследованию концепта «свобода» в русской и китайской лингвокультурах. Целью данного исследования является выявление национально-культурной специфики концепта «свобода» посредством исследования толкования, этимологии понятия, синонимических и антонимических рядов, сочетаний и фразеологизмов, а также на основании результатов ассоциативного эксперимента. В ходе исследования в русском языке и китайском языках было выявлено по 5 основных когнитивных признаков концепта «свобода». Ассоциативный эксперимент показал, что ассоциации с концептом «свобода» в двух лингвокультурах схожи. В первую очередь концепт «свобода» ассоциируется в обеих культурах с «духовной», «интеллектуальной» свободой, а не со свободой «физической». Во-вторых, концепт «свобода» в обеих лингвокультурах связан с возможностью и правом выбора. В-третьих, в обеих лингвокультурах существует взаимосвязь между концептом «свобода» и концептом «ответственность».

1. Introduction

Today the concept of freedom cannot be more relevant, because democratization has opened opportunities to constructively share opinions, compare various common viewpoints and approaches, which is crucial for exploring new pathways towards freedom and social progress in general. Freedom-related issues are emerging in almost areas of public life, be it political, economic, social, or spiritual. Thus, democratization has drawn the focus to individual’s interests and those of different national and ethnic groups; the society began to frequently address such phenomena as freedom of speech, liberal freedoms, or freedom of choice. Democratization of religious institutions granted societies a tangible guarantee of artistic freedom in research, education, and culture, as well as encouraged a necessary ethic environment for individuals to comprehensively implement their talents and abilities.

2. Research methods and principles

The methodology of this study is based on an interdisciplinary approach that integrates the methods of cognitive linguistics and linguocultural studies, in particular, definitional, componential, etymological, as well as associative and comparative methods of analysis. The research refers first and foremost to monolingual and etymological correlations (synonyms and antonyms), as well as collocations and set phrases; historically, the latter have captured the most striking national value landmarks of Russian and Chinese society. Thirdly, an association test was carried out to identify specific national and cultural traits of the concept of freedom, as well as its main cognitive aspects.

3. Main results and discussion

Over the recent decades, linguistics have focused their attention on studying the relationship and interconnection between individuals as representatives of a particular linguistic and cultural community and language as a tool for understanding the surrounding world. These researches are conducted within the framework of such interdisciplinary scientific fields as cultural linguistics and cognitive linguistics. These fields of study are based on an anthropocentric paradigm that has imposed a human-centric framework in linguistics, driving the focus towards individuals and their place in culture, since human beings and their linguistic personality are the focal center of culture. In other words, the man-language dyad and the links between its components are the center of attention in both fields; eventually, however, the dyad would be transformed into either the man — language — cognition triad in cognitive studies or that of man — language — culture in language and culture studies respectively.

V. V. Vorobyov, V. V. Krasnykh, A. A. Leontiyev, V. A. Maslov, I. G. Olshansky, Yu. S. Stepanov, V. N. Teliya, Z. D. Popova, I. S. Sternin, A. Wierzbicka, N. Evans, W. Croft, V. Bonvillain, A. J. Greimas, etc. extensively explored methods of cognitive linguistics and language and cultural studies in their works , .

In recent years, both cognitive linguistics and studies of language and culture have been extensively investigating concepts and their verbal manifestations.Though it evolved as a linguistic term long enough in the 1990s, the notion of a concept is still missing a comprehensive definition. This is demonstrated by numerous definitions of the term concept in the works by different authors. V. I. Karasik, for example, identifies a concept as "a set of mental entities representing fragments of meaningful, recognizable, typical experience stored in human memory" . В. V. Krasnykh defines a concept as "an utterly abstract idea of a "cultural object" lacking in a visual prototype, although allowing for some visual associations" .

Yu. S. Stepanov proposes a definition from a cultural perspective: "a concept is like the core of a culture stored in an individual’s mind — what brings the culture into an individual’s mental world... A concept is a basic unit of culture in human mental world" .

Many researchers believe that the reason why a concept is still missing a universal definition is that scholars highlight one or another particular aspect of the term by placing it into the focus of their definitions.

Despite numerous interpretations and approaches to concepts, linguistic and cultural studies, as well as cognitive linguistics appeal to the idea of human mind. Since "mind is the interface of language and culture, ... any linguistic and cultural study is a likewise cognitive study" . In other words, these two approaches do not exclude each other; in contrast, they complement each other, because any concept is existent in human mind, determined by the cultural environment and verbalized in language.

This study envisions a concept as a mental unit of human experience that reflects specific culture of a particular community (Chinese and Russian in our case) — their perception of freedom in its social and political sense.

According to Z.D. Popova and I.A. Sternin, concepts are established in human mind in the process of cognitive activities, including by way of communication, and shape the foundation of conceptual spaces . To elucidate what is inside a concept in native speaker’s mind, we should consider the entire range of concept-relevant texts and linguistic devices used to express this concept .

The concept of freedom is the main concept of culture with vivid figurative, axiological, and associative symbolism; this concept plays an important role in the value framework of Chinese and Russian nationals and is embedded in their conceptual space.

We suggest looking at the definition of freedom in S.I. Ozhegov's monolingual dictionary:

FREEDOM, -s, fem.

1) in philosophy: the ability of a subject to demonstrate their will based on their awareness of natural and social laws;

2) absence of any restrictions or constraints imposed on social or political life and activities of any group, society as a whole or its members;

3) absence of any restrictions or constraints wherever;

4) the situation of being neither imprisoned nor held in captivity .

Another dictionary of contemporary Russian language describes the meaning of freedom as follows:

FREEDOM 1. absence of political or economic oppression, restrictions and constraints in public life; 2. independence of a state, sovereignty; 3. absence of serfdom, slavery; 4. the situation when an individual is not imprisoned, not held under arrest or in captivity; 5. absence of any dependence on someone, ability to act at one’s own discretion or desire; 6. absence of prohibitions, restrictions; 7. getting rid of anything that imposes constraints, binds, or overburdens someone; 8. the ability of a subject to demonstrate their will amid understanding the laws of nature and society (in philosophy); 9. at ease, without difficulty; 10. simplicity, effortlessness (of posture, movements, etc.); 10. ease, relaxion, absence of tension (to behave, to deal with, etc.); || excessive relaxation, effortlessness; 11. coll. liberty, vastness, pleasure; 12. coll. time without work or other activities, leisure .

Apparently, usage in philosophical and political contexts are the first described in both dictionaries, whereas physical and spiritual freedom is shifted to the background. An explanation of this fact is that Russia’s political structure and social relations have undergone transformations in the course of different historical events; eventually, Russian people recorded these shifts in the minds to associate them with their historical past, changing political situation, and other social phenomena.

The Modern Chinese Dictionary provides a more neutral interpretation for freedom as a concept:

1) the condition of someone who is free;

2) the ability to act or think without external restrictions;

3) exemption from any moral or physical obligations .

In contrast to Russian dictionaries, this definition includes physical and spiritual freedom, meanwhile excluding political and philosophical one. However, we would note that China has several teachings that are the cornerstone of culture and value systems; in addition, there are dedicated dictionaries of philosophical terminology. Since ancient times, three fundamental philosophical teachings — Confucianism, Taoism and Chan Buddhism — have coexisted in China to exercise a huge impact on China’s culture. Confucius and his followers envisage human personality as part of the state and its society that are governed by a wise emperor who is guided by Reason and Law. To adherents of Taoism, an individual’s natural development as part of nature and the universe is an ideal; Chan Buddhism declares that all a human would need to discover the truth by their internal eyesight is "a revelation" resembling a "flash of lightning in the night". These three teachings, that have shaped the foundation of Chinese value system, are explicitly referred to in the Chinese adage: "The Chinese are outside Confucians, inside Taoists, and Buddhists at death". This allows us to conclude that the concept of individual freedom is non-existent as opposed to what is "above and beyond". In order to find "their own self", a person needs to get rid of self-sufficiency claims and dissipate in "What Is Above". In other words, the three teachings stipulate that "Someone Above" would task an individual with a mission on earth to maintain the world’s equilibrium and balance, rather than the individual would make choices or decisions at their own unconstrained will.

The analysis of the etymology of freedom as a concept in Russian and Chinese revealed similar etymological meaning. The Etymological Dictionary of the Russian Language defines the origin of the term freedom as having the same root as in pronoun svoy "own". The original meaning of the concept comes down to "a state of subordination to one’s own self (only)", "being on your own, at your own disposal" . Chinese "freedom" 自由[zìyóu] includes hieroglyphs 目由 where 目 [zì] means "yourself, in person; by oneself; to your own desire" and и 由 [yóu] means "by way of", i.e. "by way of your own self" , .

The analysis of synonyms and antonyms demonstrates that Russian synonyms and antonyms outnumber those in Chinese; however, there are synonyms and antonyms with similar meanings. Synonyms: 1. independence 自 主 [zì zhǔ]; 2. free space 自 在 [zì zài], and antonym 奴役 [nu yi] slavery.

At the second stage of our analysis we studied Russian and Chinese collocations and set phrases for the concept of freedom to highlight cognitive properties.

The study identified the following 5 key cognitive properties in Russian: "political freedom", "legal freedom", "physical freedom", "spiritual freedom", and "restriction of freedom".

These cognitive properties are reflected in the following combinations:

1) adjective + freedom, e.g. democratic freedom, unprecedented freedom;

2) freedom + noun, e.g. freedom of speech and press, freedom of action;

3) noun + freedom, e.g. the idea of freedom;

4) verb + freedom, e.g. to struggle for freedom, to breathe freely, to deprive of freedom.

In addition, the following set phrases demonstrate the cognitive properties of "physical freedom", "spiritual freedom", and "restriction of freedom", e.g. to give a loose to one’s tongues, to stretch the wings, to be one’s own master, as free as the wind in the field, as free as a bird, to keep somebody on a short leash; to twist somebody’s hands; to step on your throat.

The analysis of Chinese language also revealed 5 key cognitive properties: "political freedom", e.g. 人 身自由 "personal freedom"; "legal freedom", e.g. 放虎归山 "to let the tiger into the mountains" (lit.: to release a conman to freedom); "physical freedom" and "spiritual freedom", for e.g. 闲云孤鹤 "a free-flowing cloud and a wild (lonely) crane" (lit.: not bound by any obligations, free; complete freedom), 曳尾涂中 "to drag your tail in mud" (lit.: to live an infamous, yet freely life) and "restriction of freedom", e.g. 名缰利锁 "wealth constraints, fame binds" (lit.: absence of freedom due to wealth and fame) , .

By analyzing conceptual properties of "physical freedom" and "spiritual freedom" in the Russian and Chinese languages, we revealed that in both languages these concepts are similarly expressed by comparing human freedom with freedom of animals or nature, e.g. Russian as free as a wind in the field, as free as a bird or Chinese 鱼 在 水 里 畅 游 "the fish is swimming in water freely and pleasantly", 老 鹰 在 高 空 翱 翔 "an eagle is flying high in the sky", 骏 马 在 草 原 任 意 驰 骋 "the stallions are freely dashing through the steppes", 濠上 "above the Hao River" (meaning "at liberty") , .

3.1. Survey

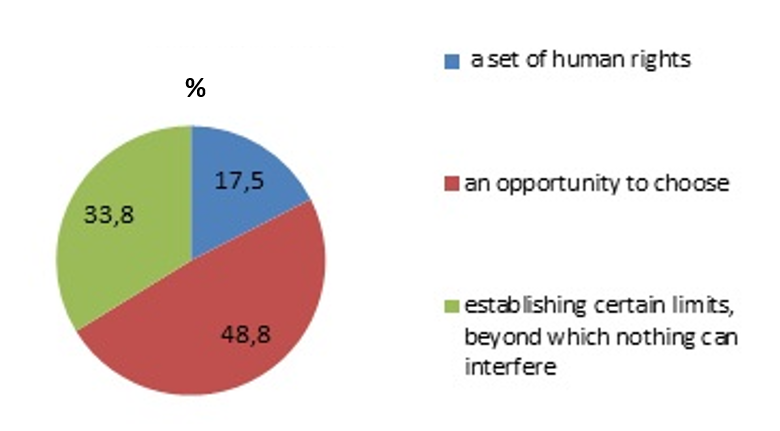

Figure 1 - Personal freedom is… (Russian students)

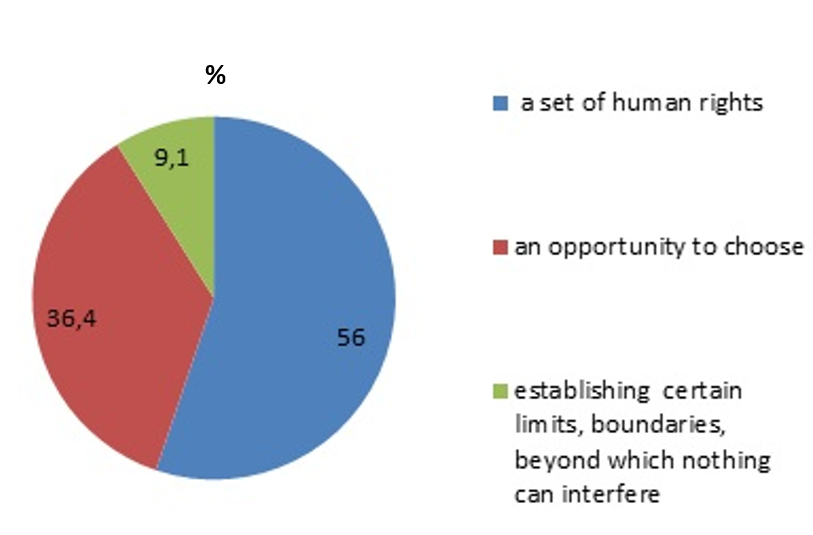

Figure 2 - Personal freedom is… (students from China)

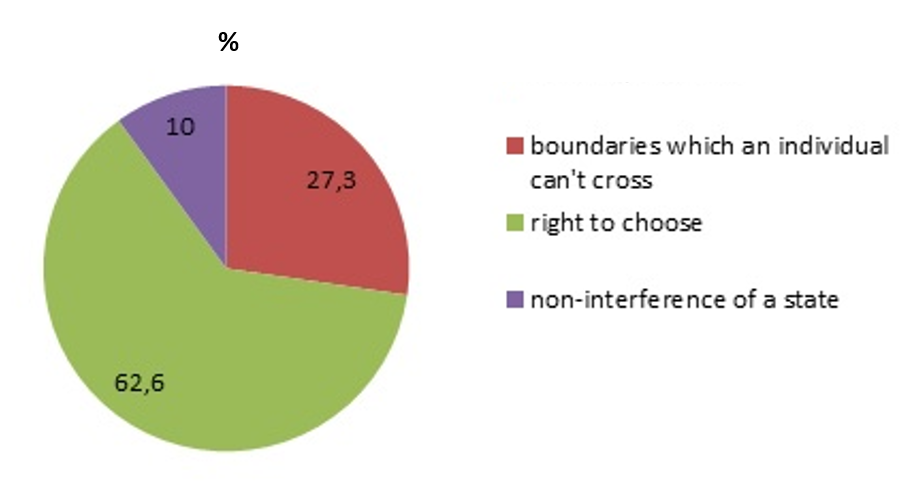

Figure 3 - The conditions obligatory for personal freedom (students in China)

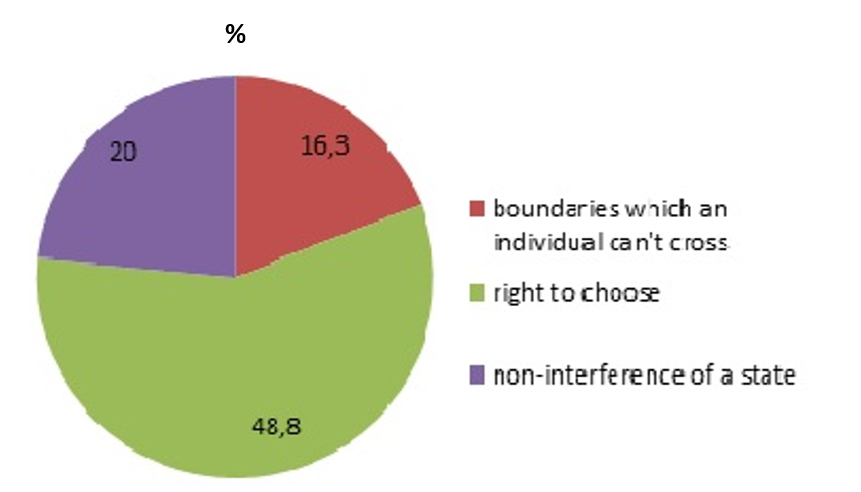

Figure 4 - The conditions obligatory for personal freedom (students in Russia)

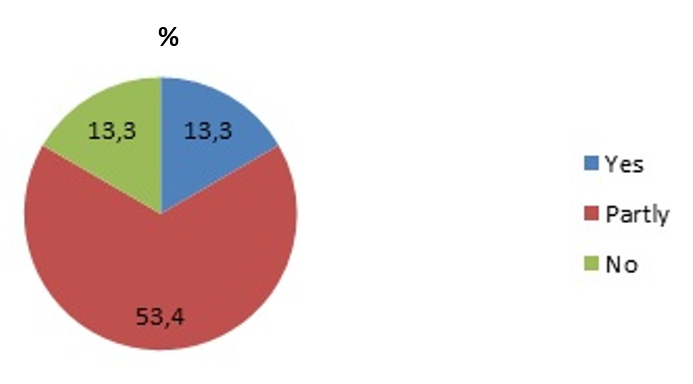

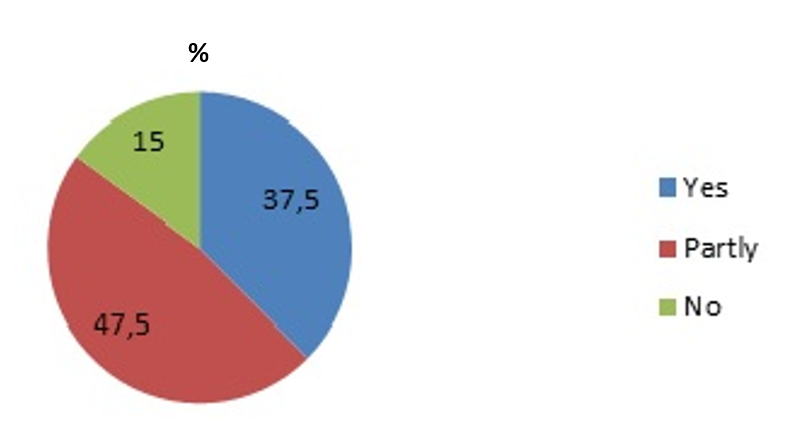

Figure 5 - Do you link the notion "freedom" with the notion "democracy" (students from China)

Figure 6 - Do you link the notion "freedom" with the notion "democracy" (students from Russia)

4. Conclusion

Overall, the association test has justified our theoretical data. In both cultures the concept of freedom demonstrates 5 fundamental properties: "political freedom", "legal freedom", "personal freedom", "spiritual freedom", and "physical freedom". In addition, similarities were successfully exemplified; both linguistic cultures push "physical" freedom to the concept periphery, while "political freedom", "legal freedom", "individual freedom", and "spiritual freedom" are located in the center of the concept. Notably, the association test has revealed another cognitive property of the concept of freedom, i.e. "freedom of choice" to denote the ability to independently make decisions in favor of any alternative solutions, without facing restrictions or pressure, including from the government.